Armstrong-Siddeley

Words: Dave Smith, photography: as credited

There’s something exceptionally British about any car maker with a double-barrelled name – Rolls-Royce, Austin-Healey, Gordon-Keeble – and here’s one of the most British of all Armstrong-Siddeley.

Armstrong-Siddeley Motors celebrates its centenary this year. In their 40-year lifespan, they became known for high quality, solid, reliable, but rather unexciting cars – the company logo should have been a stiff upper lip – despite some fairly cutting-edge technology.

A-S was based in Coventry, the British Detroit, and came about through some large industrialists shuffling the deck. John Davenport Siddeley came to the automobile field, as many Victorians did, through bicycles. He worked for Humber Cycles before moving to the Pneumatic Tyre Company, but left when it became the Dunlop Tyre Company and set up on his own as the Clipper Tyre Company which later became the Continental Tyre Company. I hope you’re keeping up – there’s plenty more deck-shuffling to come!

At the turn of that century, Siddeley and the Hon. John Scott Montagu each drove a British-built Daimler on Clipper tyres on a 1,000-mile reliability run as a publicity stunt. Both completed the event without punctures, which was great publicity for Clipper, and turned Siddeley into an avid motorist.

In 1902, he formed Siddeley Autocars, adding British-built bodies to Peugeot running gear, but was soon designing his own mechanicals and having them built by Wolseley. In 1905, Siddeley and Wolseley joined forces to create Wolseley-Siddeley, with Siddeley as sales manager alongside works manager, Herbert Austin. The two companies were a square peg and a round hole, and Austin left to forge his own path in 1906, while Siddeley left to join the Deasy Motor Car Manufacturing Company in 1908. It took some legal back-and-forth to get Wolseley-Siddeley to stop using his name, but once they did, he added it to Deasy’s to make Siddeley-Deasy, even though Captain Deasy had already resigned. Shuffle, shuffle, shuffle…

1933 Armstrong-Siddeley Special (Allen Watkin)

1934 Armstrong-Siddeley Special saloon (Andrew Bone)

1927 Armstrong-Siddeley Short 18 (Steve Glover)

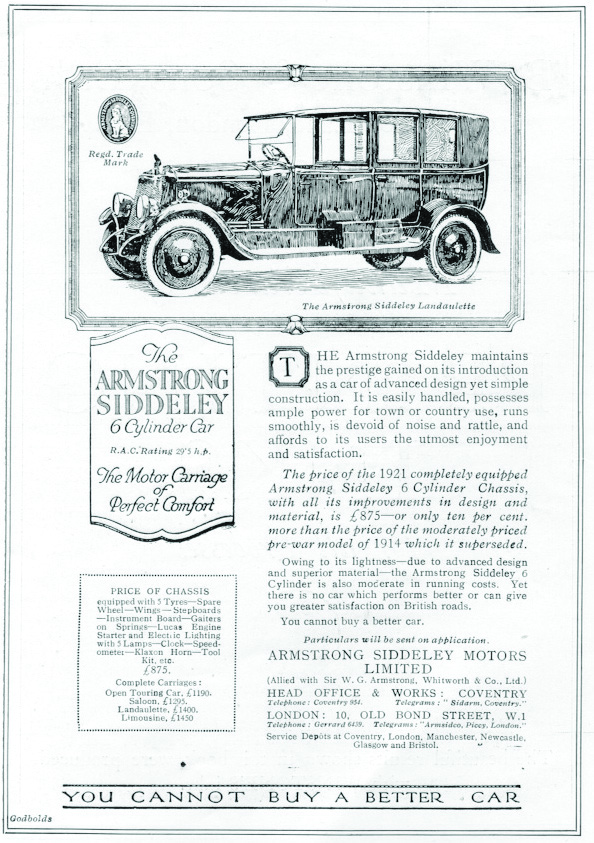

Deasy already had a reputation for quality, and in 1911, a Siddeley-Deasy 14/20 completed a 15,000-mile endurance test around Brooklands, averaging 35mph and 23mpg. Fans of these cars included luminaries such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Lionel de Rothschild. The famous Sphinx logo was born in 1912 when a journalist referred to a Siddeley-Deasy’s Silent Knight sleeve-valve engine as “silent and inscrutable as the sphinx”. Siddeley liked that reference, and the sphinx adorned all his cars thereafter.

Soon, the black clouds of war covered Europe, and the company focused on powering those new war machines: aeroplanes. S-D built 90hp V8s and 140hp V12s for the RAF, while the strong S-D chassis made good ambulances. In 1916, they built a 200hp water-cooled six that would later be called the Puma, beginning a long-running theme of naming Siddeley aero engines after big cats.

In the meantime, Siddeley had imported a Marmon, parked it at his house, and invited his designers and engineers to be “inspired” by this luxurious American machine. This led directly to the development of the 30hp Siddeley Six, and orders began flooding in after Armistice Day, but the deck was about to get shuffled again…

Back in 1847, William G. Armstrong founded a Tyneside factory that made everything from cranes to bridges to guns. In 1882, he merged with shipbuilders, Charles Mitchell, to form Armstrong-Mitchell & Co, which merged with engineering company, Joseph Whitworth, in 1897 to make Armstrong-Whitworth. Yes, that Whitworth, who gave his name to the bolt sizes and threads that confuse mechanics to this day. The new company began making cars in 1902, and opened an aeronautics branch that became Armstrong-Whitworth Aircraft in 1913, which merged with Vickers in 1927 to form Vickers-Armstrong Ltd. Shuffle, shuffle…

1935 Armstrong-Siddeley Long 15

1931 Armstrong-Siddeley 12

1937 Armstrong-Siddeley 17hp special

1938 Armstrong-Siddeley 17hp (Steve Glover)

The first Armstrong 8hp car in 1902 was short-lived because, in 1904, Armstrong-Whitworth bought out the London-based Wilson-Pilcher motor company, moved production to Tyneside, and stuck their own name on the 12/16hp 2.7-litre four-cylinder and 18/24hp 4.1-litre six-cylinder Wilson-Pilcher machines. The first car built under A-W auspices was the 1906 28/36, with a water-cooled 4.5-litre sidevalve four, followed, in 1908, by a 5.0-litre 30hp and 7.6-litre 40hp. Subsequent new models featured such modern tech as pressurised lubrication and electric lighting, and built themselves a reputation for quality. Everything halted for wartime production, after which the deck got shuffled yet again…

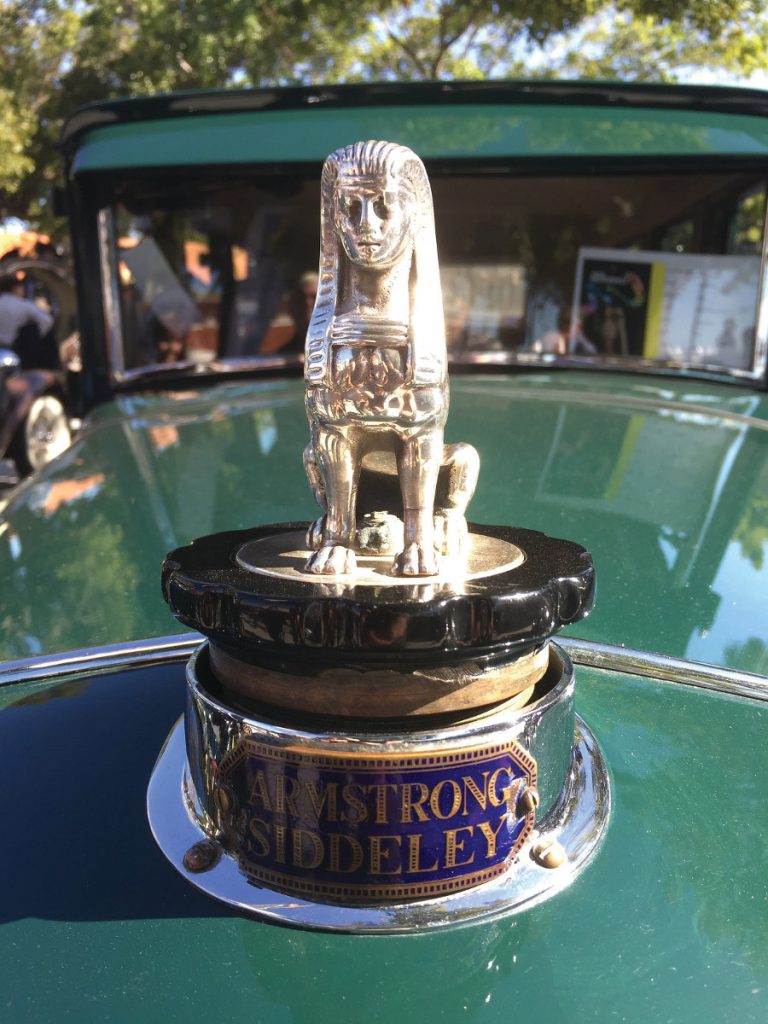

In April 1919, Armstrong-Whitworth joined with Siddeley-Deasy to form the aircraft-oriented Armstrong-Whitworth Development Company Ltd. This new company’s first job was to join the parents’ automotive concerns into a new brand, Armstrong-Siddeley Motors Ltd, with Siddeley as MD, and move everything to Parkside, in Coventry.

The first fruit of this union was the 1919 5.0-litre 30hp model, and, with patronage from the likes of the future King George VI, it was clear which market they wanted. The post-war economic boom was short-lived, though, and the range expanded downwards with an 18hp model in 1921 and a 14hp in 1923. A-S seemed to regard the 14hp as a small, cheap model, even though it was still rather large and expensive, but its rugged build made it popular for export.

1947 Armstrong-Siddeley Lancaster

1948 Armstrong-Siddeley Hurricane (Andrew Bone)

Armstrong-Siddeley radiator cap

By the mid-Twenties, the range was revamped, and soon included 15hp and 12hp cars. Things were going so well that the corporate deck got another shuffle, when Siddeley bought Armstrong-Siddeley and Armstrong-Whitworth Aircraft in 1927, followed by Avro in ’28. It was around then that Siddeley got together with WG Wilson to create Improved Gears Ltd. Wilson had invented the pre-selector gearbox, which would become one of the most significant features of Armstrong-Siddeley cars for decades.

The pre-selector gearbox was halfway between a manual ‘box and an automatic, which was still some way off. It used a fluid coupling – the predecessor to an auto transmission’s torque converter – in place of a clutch, and the driver shifted a lever into the position of the next gear he’d require, then pushed a pedal to actually engage that gear. It was smooth, reliable, and, even though it had originally been developed for use in tanks, it was so easy to operate that Armstrong-Siddeley 30hp and 18hp models were marketed as “Cars for the Daughters of Gentlemen.” Soon it was available on the whole range, and many Wilson gearboxes have survived without rebuild to this day.

At the end of the roaring Twenties, A-S hadn’t done much roaring – they were far too respectable for that – and needed to change their image. Despite a few rally successes, and the fact that the now-famous Wilson pre-selector gearbox was being used in the likes of Auto Union grand prix cars, A-S was still seen as a little stodgy and staid.

In 1932, the Armstrong-Siddeley Special replaced the old 30hp. It used aircraft technology and materials in its new five-litre, all-alloy, 145bhp engine, and, with a light touring body, could hit 100mph. They were superb but expensive cars, and certainly helped alter a few preconceptions.

1954 Armstrong-Siddeley Sapphire export 2

1954 Armstrong-Siddeley Sapphire

In 1935, at the age of 69, John Siddeley decided to retire. He sold Armstrong-Siddeley Motors and Armstrong-Siddeley Development Company avionics to Hawker Aviation, the chairman of which was none other than Tom Sopwith. Two million pounds changed hands – although the details of this were rather opaque, and subjected to some official inquiries – and Tommy merged Hawker, Gloster and A-S to form Hawker-Siddeley with A-S Motors as a subsidiary. Shuffle, shuffle, shuffle…

Shortly thereafter, with Mr Chamberlain’s “peace for our time” proving to have a short shelf-life, military vehicles were once again in demand, and production at A-S was diverted to Wilson transmissions for tanks, and the Hawker-Siddeley Cheetah radial aero engine.

A week after VE Day – suspiciously quickly – Armstrong-Siddeley were the first British manufacturer to announce their new 1945 models. These were the Lancaster four-door saloon and the Hurricane drophead coupe, both with 16hp or 18hp engines, and named after some mighty machines built by Hawker. Then came the similarly patriotically named Typhoon and Tempest coupes, and the rather less romantically titled Whitley in 1949, named for the Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley bomber. The Whitley was still aimed at the wealthy in saloon or limousine styles, but was even built as a ‘utility coupe’ – a pick-up truck – for export.

After being first to market after the war, A-S didn’t change much over the following years, believing that post-war austerity would soon end. In 1952, they introduced the Sapphire 346, a large, beautifully built, luxurious four-door with a 3.4-litre OHV straight six, but against stiff competition from Bentley, Jaguar, Daimler and Rover, this cornucopia of leather and walnut struggled to find its market.

In 1955, A-S released the smaller Sapphire 234 and 236. Both had 2.3 litre engines (although the 234 was a four-cylinder and the 236 a six-cylinder…) and were handsome and modern looking, but they weren’t traditional enough for the old A-S customers, yet too traditional to appeal to new ones.

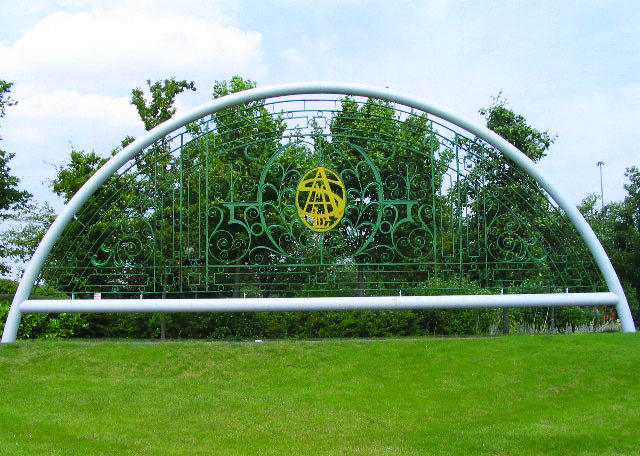

Ironwork from the Parkside factory gate still on display (E Gammie)

1958 Armstrong-Siddeley Sapphire 234 (Steve Glover)

As sales slackened, the board couldn’t justify the R&D costs of creating a new model, especially as Hawker-Siddeley needed every penny for development in the new jet age. In a last-ditch attempt to retain their old customers, they modernised the 346 into the majestic 1958 Star Sapphire. Too late. The new Star Sapphire’s £2,500 price tag was into Bentley and Rolls territory, but A-S was making barely £50 profit per car. With fewer than 1,300 cars produced between 1958 and 1960, it was no surprise when the accountants halted production and closed the doors in July 1960.

The cards were still being shuffled, though. Later that year, Armstrong-Siddeley and Bristol Aero Engines merged to form Bristol-Siddeley, itself swallowed by Rolls-Royce in 1966, who sold everything pertaining to Armstrong-Siddeley cars to the Armstrong-Siddeley Owners Club in 1972. Hawker-Siddeley Aviation was still going strong until 1977, when they became founder members of British Aerospace, and the Siddeley name finally vanished. Their old Parkside car factory has long since been demolished to make way for a university tech campus.

It was a sad and ignominious end for a company that traded on such core British values of quality, refinement and reliability – it weathered decades of boardroom shuffling, but, in the end, folded its hand in shame-faced silence.