Lanchester

Words: Dave Smith, photography: as credited

It’s one of the most history-making, ground-breaking names in British automotive engineering, yet it’s been allowed to fall into obscurity.

Do you want to start a heated debate/fight at your car club meeting? Just ask who built Britain’s first car, then go and find a table under which to hide. It seems that, arguably, the first proper ‘car’ was built by Frederick Lanchester.

Born in 1868 in south London, the middle of eight children, Fred was a gifted scientist and engineer, and won a scholarship to the Royal College of Science. At the age of 21, he joined the Forward Gas Engine Company in Birmingham, where he made some very successful refinements to the company’s engines, and, in 1892, resigned to try to sell his gas engine patents in America. This wasn’t successful – mains gas was expensive in the US, and rare outside major cities – so he came home, set up his own workshop and did subcontract work for various companies, including Forward.

In 1889, he visited the Exposition Universelle, the World’s Fair in Paris. After walking through the grand entrance to the exhibition – the new Eiffel Tower – he saw something that really sparked his imagination: a new machine called the Benz Patent Motorwagen MkIII.

Like any good engineer, he knew he could build it better, and, in 1893, designed and built a single-cylinder engine that he fitted to a boat. Within a year, he had the backing to set up a new company, designing and building cars.

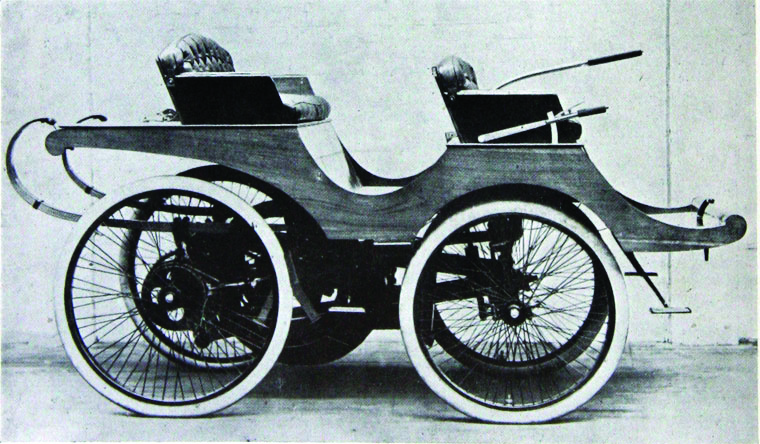

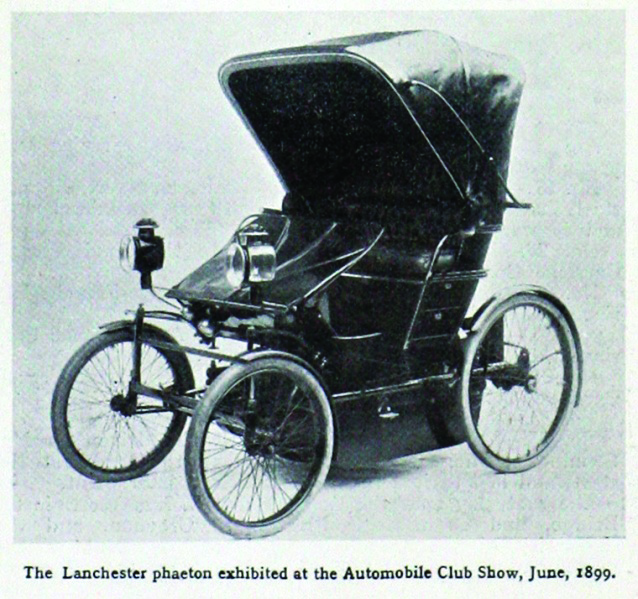

By 1895, he had a four-wheeled prototype with a 5hp engine that was to become Britain’s first car. Not a motorcycle or three-wheeler, not a carriage with an engine instead of a horse, but a motorcar, designed as such from the ground up. The engine was ingenious, with a single piston attached to two con-rods, driving two counter-rotating cranks and flywheels, so it ran very smoothly. It had its first road-test in early spring, 1896, before the single-cylinder engine was replaced with a two-cylinder, 8hp flat-twin version in 1897. Shortly afterwards, he moved to a new home and workshop in Birmingham and built a second car, the Gold Medal three-seat phaeton, with a similar power plant.

With these machines in his portfolio, he secured financial backing from the likes of the Pugh brothers, of Rudge-Whitworth cycles, and the Whitfield brothers and, to follow a pattern, brought two of his own brothers in on the deal. Thus, the Lanchester Engine Company Ltd, with Frederick and his brothers, George and Frank, on the board, was incorporated in late 1899.

1895 Lanchester – the first car

1899 Lanchester phaeton

The first days of the 20th century saw Lanchester making half a dozen cars with a view to production. These cars had a four-litre flat-twin with the counter-rotating cranks, air cooled using two large fans, with a three-speed epicyclic gearbox and worm drive, and were used as demonstrators before going on sale to the public in 1901. Very soon, there were models of 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18hp available, the larger engines being water-cooled.

In 1902, just seven years after building Britain’s first car, Lanchester invented a feature that wouldn’t catch on in the mainstream for another 50 years, and that you’ll struggle to find a car without today: disc brakes. Accounts vary – some say they were used on brass discs at the front wheels; others say that the caliper acted upon the clutch plate – but this was very much a first step on the road towards the braking system used almost universally by the end of that century.

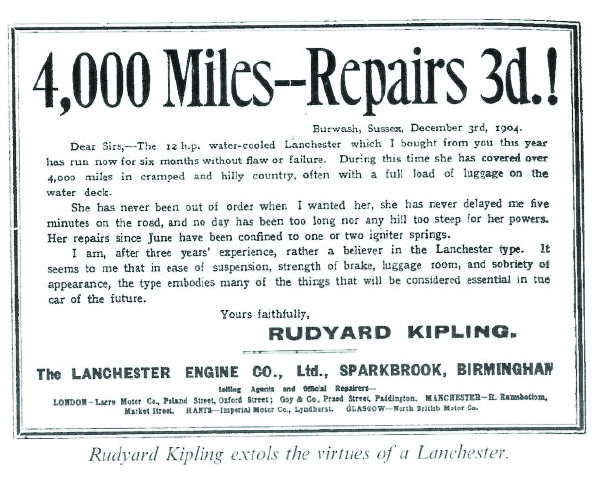

So Lanchester’s cars were highly unconventional, but also cutting-edge and of superb quality, so it found favour with the high and mighty of the day. By 1904, these included the Marquis of Anglesey, His Grace the Duke of Portland, the Most Hon. The Marquis of Zetland, and Major Lindsay Lloyd, R.E., on behalf of the War Office. One of the first celebrity owners was Rudyard Kipling, who ordered a 10hp, which was delivered to his Sussex home personally by George Lancaster in 1902.

Somehow, despite seemingly having found the recipe for success, and with full order books, the Lanchester Engine Company Ltd went into voluntary liquidation in early 1904. After regrouping and refinancing, the company restarted later that year under the name Lanchester Motor Company Ltd. Fred continued to invent, and came up with more solutions, still in use today, to prevent noise, vibration and harshness – his new 20hp four-cylinder used a block-mounted balance shaft, and his 1907 38hp six-cylinder used a crankshaft harmonic damper.

1901 Lanchester 12hp (Clive Barker)

1903 Lanchester 12 (Clive Barker)

1904 Lanchester Kipling ad

1910_Lanchester 28hp Landaulette (Alf van Beem)

1914 Lanchester Forty dash (Peter Turvey)

In 1909, Frederick Lanchester took a step back from his own company, becoming a part-time consultant, while also consulting for Daimler and, later, Daimler’s parent company, BSA. While still at Lanchester, Fred experimented with everything from the seemingly mundane – a newfangled steering wheel instead of a tiller was an option on Lanchesters from 1908, and became standard by 1911 – to the outrageously advanced – he was experimenting with turbocharging and fuel injection before World War I. Other advances we can thank Frederick Lanchester for include pressure-oiled bearings, forged pistons, piston rings, hardened cylinder liners, plus torsional vibration dampers and harmonic balancers. He developed independent front suspension, and was even the first to use the detachable ‘knock-off’ wire wheels of which we’re all so fond… In 1915, he took out a patent for an internal combustion engine, electric motor and generator operating on a common shaft. This was refined over the next 10 years into the 1925 ‘Petrelect’ system – yes, George created and patented the first hybrid.

As if this were not enough, he was also a genius in the then-new field of aeronautics and aerodynamics, and some of his work with aircraft became industry standard, too. In fact, the aircraft that played such a significant role in WWI, and all aircraft since, owed much to Fred Lanchester, but that’s a whole new story.

1925 Lanchester Forty

1926 Lanchester landaulette

1927 Lanchester tourer

George Lanchester played an increasingly important role in the family company in the early ‘teens, and when Frederick resigned in 1913, George took over; Frank was running the London-based sales department. Occasionally, Frederick’s high-tech developments were a little too high-tech for a conservative buying public, and George began making Lanchesters a little more conventional. That doesn’t mean dull, though; the first development was a new six-cylinder, 5.5-litre 40hp engine that developed 78bhp at 1,800rpm. This new Lanchester Forty had a conventional long bonnet with the engine beneath, and George lapped Brooklands at 115mph in one of the two 40s built for racing.

Sadly, such frivolities were soon replaced by the sombre business of war, and Lanchester’s Sparkbrook factory spent ‘the Kaiser War’ turning out artillery shells, aircraft engines and armoured cars based on their own 38hp chassis.

After Armistice Day, production of the Forty restarted. It was the only Lanchester model available, and, with its 6.2-litre overhead cam engine, was a top quality, refined, sporting tour de force. It was also, however, stunningly expensive, pricier even than Rolls-Royce’s Silver Ghost, so the market was limited. This led to the smaller Twenty One joining the range in 1924, with a 3.1-litre six-cylinder, four-speed ‘box and four-wheel brakes. This grew into the 3.3-litre Twenty Three in 1926 and, two years later, the Forty was replaced by the 4.4 straight-eight Thirty.

1929 Lanchester sports tourer in Haynes Museum (Hugh Llewelyn)

1930 Lanchester Thirty straight eight

1934 Lanchester Ten (Steve Glover)

1935 Lanchester, Daimler straight-eight, Vanden Plas touring body

This straight-eight was the last of George Lanchester’s designs as, during the late Twenties, the depression began to erode the market for such top-end machinery. Within weeks of a glamorous display at the Olympia Motor Show in 1930, the company’s bank called in its £38,000 overdraft, and Lanchester was left high and dry. This forced the sale of the company, and their Sparkbrook neighbours, BSA, bought the company for a song in 1931. BSA packed Lanchester up and sent it to Coventry to live with its new stepsister, Daimler.

Lanchester’s salad days of innovation and market leadership were gone, and a future of badge engineering and playing second fiddle lay ahead. The first new model, the Lanchester Eighteen, was designed by George but owed more than a little to the Daimler Light Twenty. The 1933 Lanchester Ten was a fancified version of the BSA 10, and the 1937 Lanchester Fourteen was basically a facsimile of the Daimler New Fifteen.

Once again, war cast its shadow over an already troubled Daimler/Lanchester alliance, and with the Luftwaffe taking a particular interest in Coventry’s manufacturing plants, times got even harder. After the war, with much of Coventry in ruins and steel in restricted supply, Daimler went back to making luxury cars and limousines while Lanchester got to make the new LD10, a 1,300cc four-door saloon. It looked a lot like a halfway house between the Ford Prefect and the Ford Pilot, which is unsurprising given that Briggs of Dagenham, who also made the aforementioned Fords, made the LD10 bodies.

The next new model would be five years later, with the 1950 Lanchester Fourteen and the export version, the Leda. Daimler was still suffering, though, having taken a kicking from post-war austerity and Purchase Tax on top-end cars, and introduced the new, compact Daimler Conquest in 1953… just after Purchase Tax was reduced. The Conquest was based on the Fourteen, and was effectively competing for the same buyers.

1937 Lanchester Eleven (Andrew Bone)

1937 Lanchester Fourteen Roadrider (Steve Glover)

1947 Lanchester LD10, Briggs body (Steve Glover)

1951 Lanchester LD10

1951 Lanchester Ten

1953 Lanchester Leda (Clive Barker)

It seemed that Lanchester, ever the second fiddle to Daimler, had been sabotaged from within. They shambled on for a couple of years until 1955 when, with a new model codenamed the Sprite at the prototype stage, struggling Daimler simply phased out the Lanchester name. Throwing the Lanchester weight overboard wasn’t enough to keep Daimler aloft, though, and BSA sold all its Daimler interests to Sir William Lyons over in Browns Lane in 1960.

A corporate pass-the-parcel game saw Jaguar merge with BMC to form British Motor Holdings in 1966, then with Leyland and Rover to make BLMC in 1968, then the nationalised British Leyland in the Seventies. It was privatised again in 1984, taken over by Ford in 1990, then lumped in with Land Rover when Ford bought that in 2002. Ford sold both to Tata in 2008, whereupon they were merged to form Jaguar Land Rover in 2013.

Somewhere, in a dusty filing cabinet somewhere in Coventry, JLR (and therefore Tata) still own all the rights to the Lanchester Motor Company Ltd. Is this great name forever destined to exist solely on paper, another forgotten soldier from the massed ranks of British automotive heritage, or might it one day be dragged out, dusted off and maybe applied to some cutting-edge experimental or prototype vehicles from the JLR stables? I think Frederick would approve of that.

Frederick Lanchester died on March 8th, 1946. In his later life, among countless awards for engineering prowess, he was a Fellow of the Royal Society, an Honorary Member of the Royal Aeronautical Society and the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, and had been President of both the Junior Institution of Engineers and the Institution of Automobile Engineers. His obituary from the IME said that, had his contemporaries accepted his early research, Britain would have been a decade ahead of the rest of the world in aeronautics. Of his automotive work, they said: “For the first 10 years in this field Lanchester introduced in rapid succession numbers of features still regarded as the best practice, and probably no other single person in this country has been responsible for so many pioneer inventions of value in this particular branch of engineering.”

There’s a large monument to Lanchester on the Birmingham site where Fred built that first car way back in 1895, and a commemorative blue plaque on his former Sparkbrook factory. Coventry’s Lanchester Polytechnic was also named in his honour, though later renamed Coventry University, though the imposing Lanchester Library is still on campus. Lanchester’s name should probably be held in the same esteem as that of Brunel, Stephenson, Whittle or Watt, yet he seems destined to remain in relative obscurity. Maybe, one day, Frederick Lanchester will be looking up at you from the back of a £50 note and you’ll have cause to think of how very different the automotive and aeronautical landscape might have looked without him.