Singer

Words: Dave Smith, photography: various

Another look back at a name from Britain’s proud motoring heritage. This month, Singer: a great independent that was swallowed by the corporate machine

Think ‘Singer’, and most people will think of sewing machines. Sadly, that’s how far this once-great motoring name has fallen from the public consciousness over the past 50 years. In fact, the founder of Singer Motors Limited, George Singer, was in the sewing machine business in the late 19th century, but had nothing to do with the sewing machines of the same name – the Singer Manufacturing Company was founded in America in 1851.

George was working for the Coventry Sewing Machine Company when he decided that his future lay in two-wheeled transport and, in 1874, he left to start his own bicycle company with his brother-in-law. The Coventry Sewing Machine Company, incidentally, had had a similar idea of their own a few years previously, spawning the branch that would eventually go on to become the Swift Motor Company… but we digress.

This was the period when everyone who could nail together a horse cart was jumping on the bicycle bandwagon, though the Singer Cycle Company attempted to modify the traditional penny-farthing arrangement into a much safer proposition. Right at the tail end of the 19th century, the industry suffered a huge slump, at which point George turned to the latest fad: cyclecars.

The first example from the new Singer Motor Company housed a motor inside the rear wheel. This developed into a successful series of Singer motorcycles that continued until the First World War. The car range, meanwhile, went through the usual procession of spindly three-wheelers until the first four-wheeler, the 12/14, appeared in 1905. From here, the range grew, incorporating two-, three- and four-cylinder engines in various body styles, and established the Singer name in a marketplace where every town seemed to have its own car manufacturer.

It was in 1912 that things really went right with the introduction of the Singer Ten, a two-seater light car with a steel chassis, 10hp 1.1-litre four-cylinder engine, and a transaxle between the rear wheels. At the time, automobiles seemed to be diverging into large cars or small cyclecars; Singer’s Ten showed that you could have a small car, simply a smaller version of a large car, that was rugged, reliable and offered 40mpg. When it was launched at the 1912 Olympia motor show, it was an instant hit, and 50 examples – almost the entire first year’s production – were ordered by one man, William Rootes, who had previously apprenticed at Singer and subsequently opened his own dealership, and would go on to be an even more significant name in Singer’s future. Sadly, George Singer was not around to see this newfound stardom – he died in 1910.

The Singer Ten turned into quite the track star as well, being popular in hillclimbs and, in the hands of Lionel Martin, winning races and setting a whole book-full of records at Brooklands in the under-1100cc class. The Great War then came along to get in the way of this success, although the Ten did sterling service for the military across Europe and into Egypt.

By the time hostilities ceased, Singer had firmly entrenched itself in the marketplace, and came back with an extended range of 10 models. The Ten was still far and away the best seller, but a larger six-cylinder Fifteen car came along in 1922, and a budget-priced 10/26 four-seater with an overhead-valve 10hp four-cylinder in 1923.

The star of the 1926 London motor show was the new Singer Junior, a small, spindly four-seat tourer along similar lines to Austin’s soaraway Seven, but with an all-new engine – a sprightly 848cc four-pot with a chain-driven overhead cam that would form the basis for Singer engines for decades to come, and all for £150. Coupled with other advances in their 40-model range, such as independent front suspension and clutchless fluid-coupling transmissions, Singer climbed to the lofty heights of the third best-selling British marque, behind Austin and Morris.

Naturally, success is always likely to find its way to the race track, and, in 1933, a Singer nine became the first sub-1100cc car to qualify for Le Mans without a supercharger. This led to the Nine becoming (unofficially) known as the Singer Le Mans, and being very popular among sportsman racers until it grabbed the headlines in 1935 for the wrong reasons. The works Nines entered the Ulster Tourist Trophy, and all three crashed out on the same corner, with the same steering failure. Singer disbanded the works team after that.

Towards the end of the Thirties, Singer was in trouble financially, with a general recession and increased competition from Austin, Morris, Hillman and Ford putting the pressure on. In late 1936, the company was dissolved, and business transferred to a new company, Singer Motors Limited. Things were beginning to look up after that, with increased sales and a new Roadster model, until Mr Chamberlain waved his piece of paper and Singer’s factories once more switched over to war production, mostly aircraft parts.

Production picked up much where it had left off after the war, until 1948 when the new SM1500 debuted. This was an all-new, integrated-wing, streamlined car with the new 1500cc OHC engine, an engine that soon found its way into the Roadster, too. This helped with the export drive, and Singer Roadsters were popular with the Hollywood crowd – Sammy Davis Jr, Marilyn Monroe, Debbie Reynolds and Katharine Hepburn all had one.

The reflected glory from the silver screen didn’t help, though, and the company continued to struggle. Singer prices were quite high in the years of post-war austerity, and, after a brief lift in 1954 when the SM1500 was handsomely restyled and renamed the Hunter, the company was back on the verge of collapse.

Remember young Billy Rootes, the apprentice back in 1909, who went on to found the huge Rootes Group? Well, young Billy was now Sir William Rootes, knighted after his efforts during the war, and his Rootes Group had already hoovered up Hillman, Commer, Humber, Karrier, Sunbeam and Clement Talbot. In 1955, he proffered the olive branch to Singer Motors Limited, and shareholders reluctantly took it.

Rootes was a huge fan of badge engineering – a mixed grille, if you will – and after bringing Singer into the fold, the name became little more than the badge applied to upmarket Hillmans. The first post-Rootes Singer model was the Gazelle, a Hillman Minx in a posh frock with the old 1500 Hunter engine, and even that engine gave way to standard Hillman pushrod fare a few years later. The 1961 Vogue was much the same, being a posher version of the Super Minx.

When the new, squarer Arrow range was launched in 1966, the Vogue and Gazelle names appeared on fancier versions of the Hillman Minx and Hunter. In late 1964, however, Hillman’s new baby, the Imp, had been tarted up a bit and named the Singer Chamois. The Imp/Chamois should have been the car that gave Issigonis’s Mini a good kicking; instead, it was a major contributory factor to the demise of the whole Rootes Group.

Sir William, who was made 1st Baron Rootes in 1959, had died in 1964, and his son, also William, took over the company that bore his name just in time to see it begin to crumble. Labour problems with various arms of the company, including the new Imp factory in Linwood, west of Glasgow, was dragging it down, and the Imp was hardly the commercial success they’d counted on. It was just too radical in a country still happy to plod around in Morris Minors and Ford Populars, especially after the Imps got a reputation for unreliability.

Through the Sixties, American giant, Chrysler, had been gradually taking shares in the Rootes Group with a view to using them as a springboard into Europe. Their main rivals, Ford, were already global, while GM already owned Opel and Vauxhall, and Chrysler wanted a piece of the action. Chrysler had already bought France’s Simca, and bought 30% of Rootes in 1964. In 1966, Rootes Group reported losses exceeding £10 million, and Chrysler snapped up the remaining shares. By 1967, they owned the whole show and the Chrysler pentastar badge began appearing on Rootes cars.

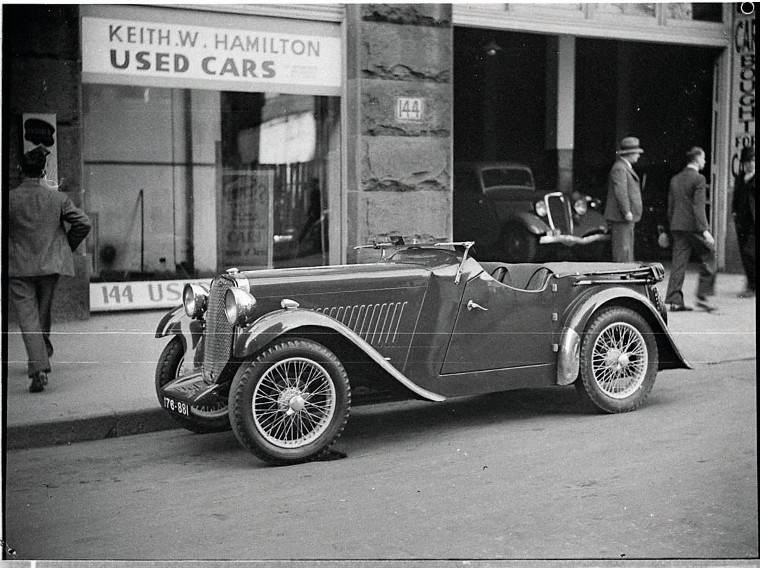

Singer Junior (1931)

Singer Porlock (1929)

In 1970, the Rootes Group was formally renamed Chrysler (UK) Ltd, and Simca became Chrysler (France). It was around this point that Chrysler top brass seemed to realise that the UK arm and the French arm were making cars that directly competed with each other, and began the process of evicting the old names. The fat lady had sung for Singer, which was the first to go, and the last Gazelles, Vogues and Chamois were sold off in 1970. Commer and Karrier were merged into a Europe-wide Dodge trucks brand, while Hillman, Humber and Sunbeam struggled on until 1976, when the range was rebranded as simply Chrysler.

By the end of the Seventies, Chrysler were in trouble at home in America, and sold their whole sorry European show to Peugeot for a dollar in 1979. Peugeot dragged the Talbot name from a dusty cupboard and rebranded all the ex-Chrysler/Simca/Hillman etc products as Talbot on either side of the channel. This farce shambled on until 1987 when Peugeot finally pulled the plug, and the 20-year-long game of corporate Three-Card Monte gasped, died, and went unmourned. It was a sad and tawdry end for many fine British marques; it’s almost a blessing that Singer was no longer around to see it.

Singer 10 (1919)

Singer 10/26 (1926)