Sunbeam

Words: Dave Smith, photography: various, as credited

This once-proud Black Country manufacturer’s fortunes went up and down like the sun itself.

John Marston was born into a well-to-do landowning family in Ludlow, Shropshire, in 1836. At the age of 15, he went to Wolverhampton, where he served his apprenticeship at Edward Perry’s tinplating and japanware outfit. At 23, he left Perry to set up on his own, buying a factory in nearby Bilston, and did so well that, when Perry died in 1869, Marston took over Perry’s factory too.

Marston was a keen cyclist, and cycle making was a booming business, so he cut himself a piece of the action and began making Sunbeam bicycles. It was his wife, Ellen, who suggested that he adopt Sunbeam as his brand name, and, in 1897, the ex-Edward Perry Jeddo Works factory became the charmingly-named Sunbeamland.

Thomas Cureton was a well-educated chap who had been apprenticed to Marston in the early days, and became his right-hand man at Sunbeamland for many years. He suggested that motor cars might be the next big thing, and perhaps Sunbeam should get on that bandwagon, too. The board of directors weren’t keen on this new-fangled idea, but Marston and Cureton treated it as a side project, drawing up plans and eventually beginning work on a prototype in 1899.

John bought a disused factory in Villiers Street, Wolverhampton, and, in 1898, his son, Charles, began making parts for Sunbeam cycles, as well as other manufacturers. This company, which Charles bought from his father in 1902, was Villiers Engineering, and would go on to patent and produce the freewheeling gear used by almost every bicycle made since. They would also produce millions of engines that powered everything from lawnmowers to motorcycles for most of the rest of the century.

Anyway, Marston and Cureton had taken over a disused coach house in a parcel of land on nearby Upper Villiers Street, adjoining what would become Charles’s factory, and set a couple of their best engineers to build their prototype. Upon completion, the two-seat, 4hp machine was tested around the local roads at up to 14mph. They built a second car, very similar to the first, which was exhibited at the 1901 National Show at Crystal Palace, and a third.

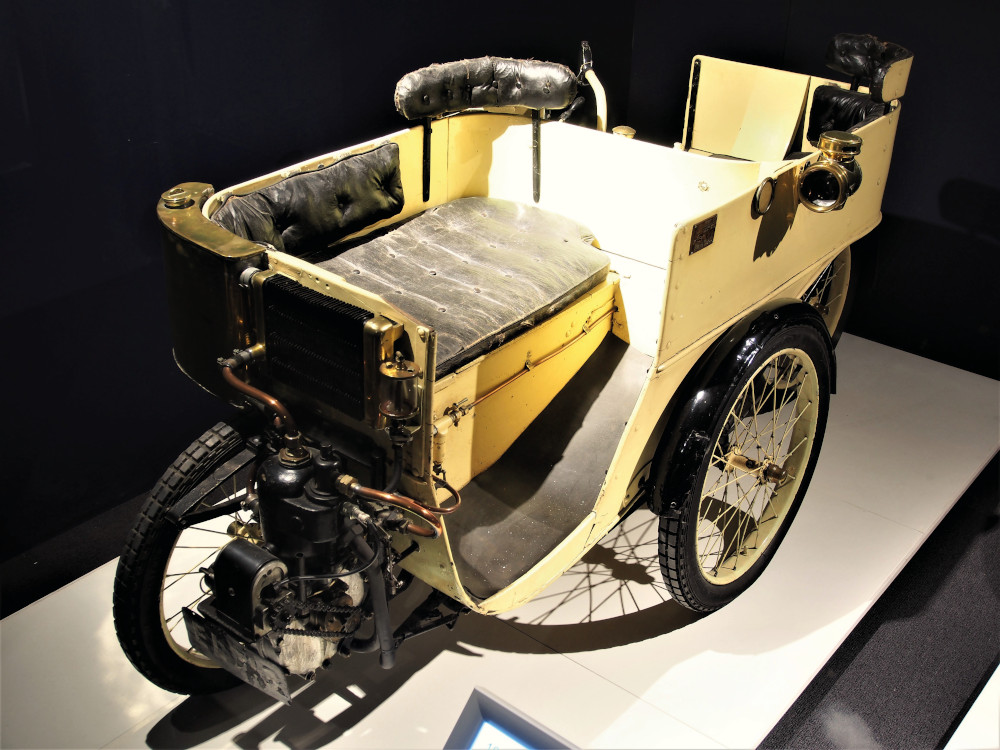

1912 Sunbeam Touring (State Library of Queensland)

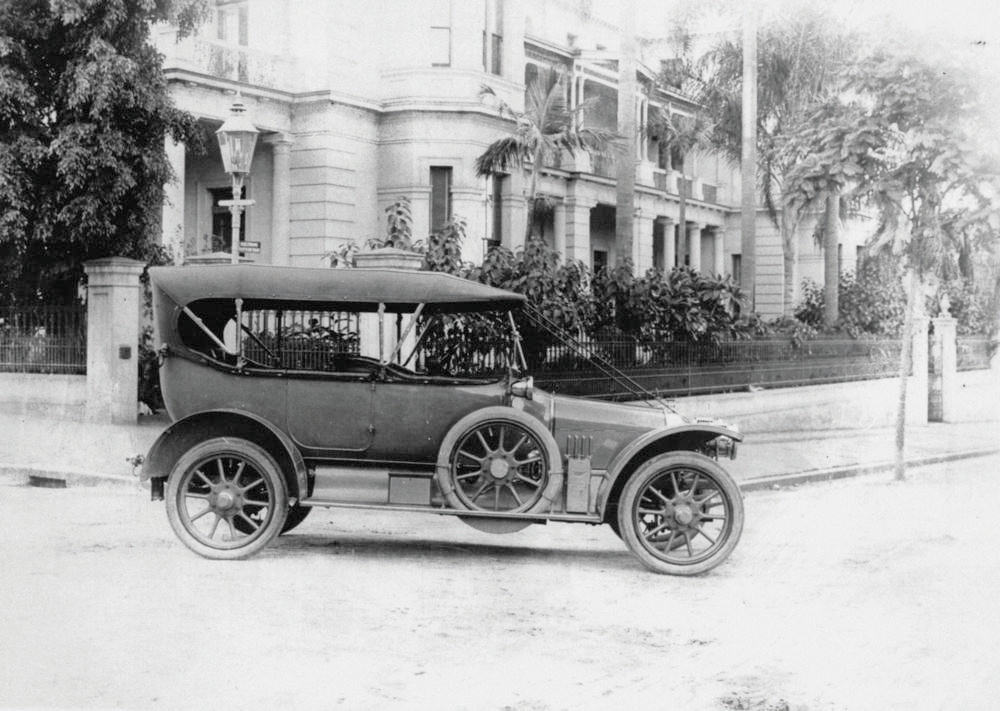

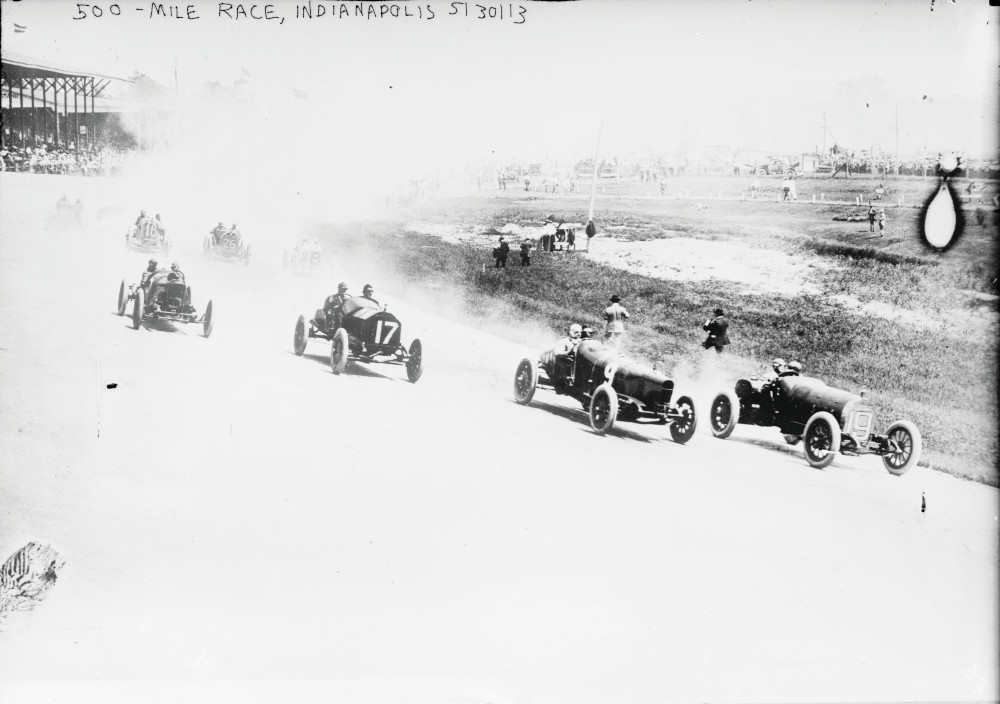

1913 Indianapolis 500, #9 Albert Guyot’s Sunbeam

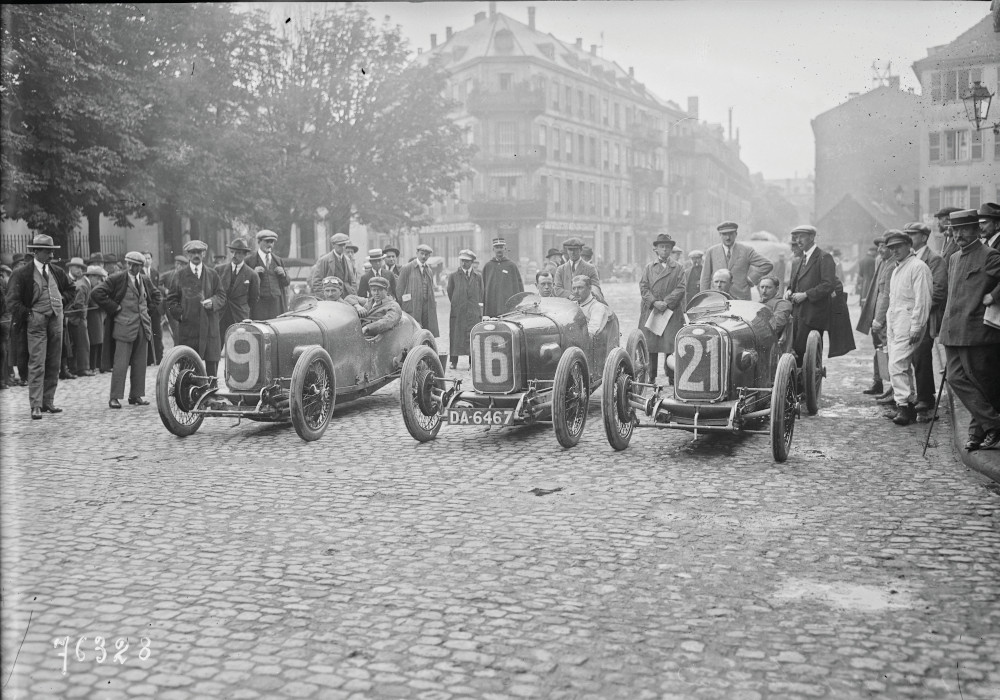

1922 French Grand Prix, Team Sunbeam

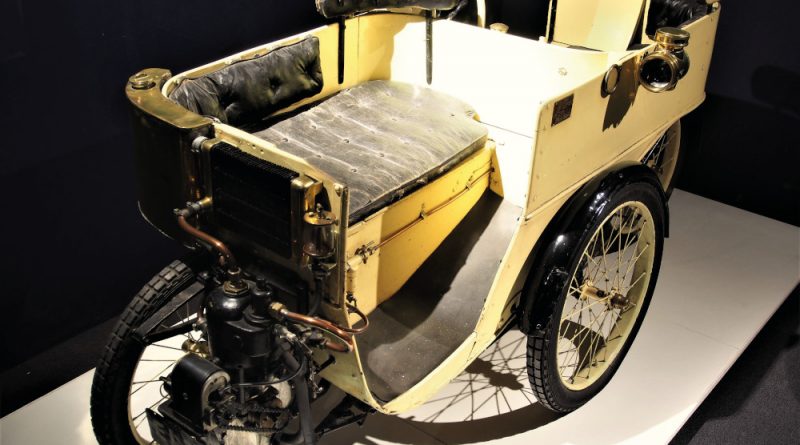

The first car to bear the Sunbeam name came about after Marston met a young architect named Maxwell Maberley-Smith at the Crystal Palace show. Maberley-Smith was displaying his new design, which, compared with the mainstream car designs, looked like an April Fools joke. His ‘sociable’ was a quadracycle, with four wheels arranged in a diamond formation. The 2.5hp DeDion engine was alongside the front wheel, driving the middle wheels via a leather belt, while the driver sat over the rear wheel, and one or two passengers sat in the middle, facing to the left. He offered it to Sunbeam as a project that was ready for production – hence avoiding development costs – and the Sunbeam-Mabley (sic) was born. It was cheap, eventually selling for £130, and sold a few hundred examples.

Meanwhile, Marston was preparing a more conventional 6hp car with bodywork by the nearby Forder coachbuilders. The automobile business was definitely taking off, and Marston sold all his japanning and tinware concerns to concentrate on cars in 1902. That same year, he employed Thomas Charles Pullinger as Works Manager, an engineer who had spent many years at Darracq in France, and designed, among other things, the water-cooled cylinder head. Pullinger persuaded Marston and the board that they should consider importing completed chassis, with running gear but minus bodywork to begin with, then with fewer and fewer imported components as they developed their own. He suggested Berliet chassis, and, late that year, the first of the 12hp, four-cylinder cars went on show.

The new cars, badged as Sunbeams, were entered in early trials to garner publicity. It worked – Sunbeam won the 100-mile Liverpool Reliability run in 1902, the London To Oxford Anniversary run, and the 1903 London To Glasgow Trial, and garnered plenty of press.

The 1903 Sunbeam was the Pullinger-designed 10/12hp model with a 2.4-litre four-cylinder engine. It was a success, and the 20 staff at the Upper Villiers Street factory were turning out 18 of the 500 guinea cars a month. A six-cylinder 16/18hp model followed in 1904, and the plant was expanded to cope.

In the spring of 1905, John Marston Ltd decided to spin off the automobile concern as a company separate from the cycles and other projects, and the Sunbeam Motor Car Company Ltd was formed, with Marston as Chairman. Pullinger had left to join Humber, and the first designs from his replacement, Angus Shaw, were by now ready to jump from drawing board to production. The first was the 1906 Sunbeam 16/20, and Angus himself drove the prototype from John O’Groats to Land’s End and back without once stopping the engine – quite an achievement. The car sold well, and once again the factory needed to expand, this time into more land on Upper Villiers Street, with a new building that would soon become the Moorfield Works.

The new 1907 25/30hp model’s release coincided with a sudden slump in the car market, and the model would only sell 11 units that year, but the new 1908 20hp and 35hp models fared a lot better.

In 1909, Louis H. Coatalen joined the Sunbeam roster. Something of an engineering prodigy, he had served at Panhard, Clement and DeDion-Bouton before moving to Humber, in Coventry, in 1901. From there, he moved down the road to Hillman, and the Hillman-Coatalen car impressed Thomas Cureton so much that, in 1909, he offered Coatalen the job of Chief Engineer at Sunbeam.

1929 Irish Grand Prix, Cpt Malcolm Campbell’s Sunbeam

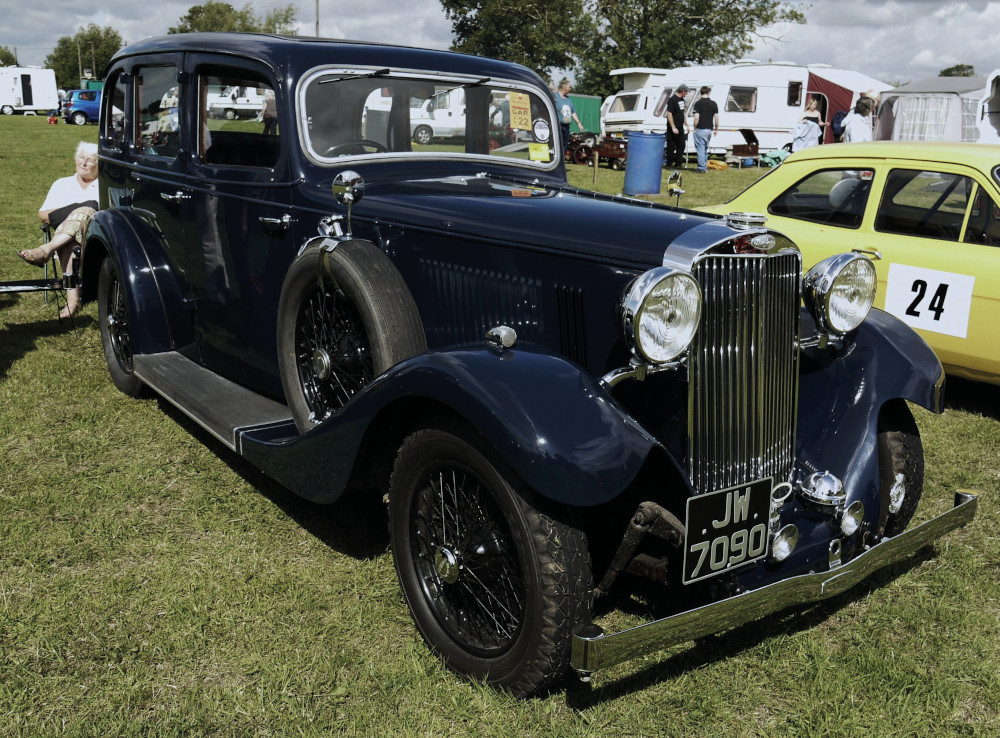

1935 Sunbeam 20 saloon

1925 Sunbeam 20_60 (Alexandre Prévot)

Coatalen brought a love of motor sport. His motto – “Racing improves the breed” – led to him entering his first design, the Sunbeam 14/20, in the RAC Ten Pound Note Trial, in which he achieved 21.3mpg on the 100-mile road section, then an average of 56.6mph around Brooklands. This led him to develop an overhead-valve, pressure-lubricated engine, then installing a 4.2-litre four-cylinder, 16-valve version of it into a racing monster called the Sunbeam Nautilus in 1910. The torpedo-shaped body led to overheating, so he designed a replacement, the Sunbeam Toodles II (apparently Coatalen’s pet name for his wife, Olive) in 1911. That Easter, it achieved 83mph at Brooklands, and beat its nearest rival, a Napier, in a match race. Toodles II won 22 prizes and records that year, giving Sunbeam some much-needed publicity. Over the next few years, Sunbeams would race everywhere from the Isle Of Man TT to the French Grand Prix, with considerable success.

Meanwhile, Sunbeam road cars were becoming ever more popular, and the company branched out into aero engines. In fact, Toodles V was powered by a monstrous airship engine, and captured two dozen records in 1913, but then more pressing concerns became apparent as war loomed. Sunbeam continued building cars, motorcycles and ambulances for the war effort, until 1916 when the Ministry of Munitions ordered them to concentrate on aircraft engines.

Immediately after the war, there was tremendous upheaval at Sunbeam. Coatalen had been made joint Managing Director alongside William Iliff in 1914. Marston had been preparing his third son, Roland, to take over as Chairman, but he died suddenly in March 1918. John Marston himself died the day after Roland’s funeral, leaving Cureton to succeed him as Chairman.

In November 1918, production of the 16 and 24hp models recommenced, but the market was hardly buoyant, and the government were rather slow in paying their wartime bills. Shortly after the war, Darracq had bought up Clément-Talbot, then, in 1920, bought up Sunbeam. Sunbeam, Talbot and Darracq operated as three individual companies under the name STD Motors Ltd, and Coatalen became chief designer across all three. Cureton retired as Sunbeam Chairman that autumn, and sadly died within a year.

Coatalen’s racing obsession was still strong, and he built Grand Prix racing Sunbeams for the likes of Henry Segrave. He built a 350hp, 27-litre airship-engined machine for KL Guinness to race at Brooklands, where it set a new speed record of 133.75mph in 1922. That car was sold to Malcolm Campbell, who renamed it BlueBird and topped 150mph at Pendine Sands in 1925. In 1926, Segrave asked Coatalen to build him a car to crack 200mph, so Coatalen put two Sunbeam Matabele 420bhp V12 aero engines, each tuned up to 500hp, at either end of a chassis with Segrave in the middle. On March 29th, 1927, Segrave took the 1,000hp machine over 203mph on Daytona Beach.

1952 Sunbeam-Talbot 90 (Steve Glover)

1961 Sunbeam Rapier (Steve Glover)

Meanwhile, Coatalen had effectively moved back to France, working at Darracq’s factory near Paris and occasionally popping back to Wolverhampton. After another land speed record project, the ill-fated Silver Bullet, Coatalen left Sunbeam in 1931. The company was still turning out high-quality, technically advanced and well-built cars in significant numbers, and even diversified successfully into buses and trolleybuses, but the unpaid war debts and a downturn in the aero side of the business dragged Sunbeam down. Sunbeam and Talbot called the receivers at the end of 1934; Clément-Talbot was still afloat, and was sold to Rootes Brothers. In July 1935, Rootes announced that they had bought the Sunbeam Motor Car Company too, though they simply closed car production at Moorfields and shelved the name.

Rootes’ main concerns were mass-production and high-volume cars, and they were early exponents of badge engineering. Years of sleight of hand and name-changing between Darracq, Clément and Talbot confused the issue no end, and Rootes began making Talbot their luxury brand (by putting fancy Talbot bodies on Humber chassis) until Anthony Lago bought Talbot of France and began also selling Talbots. So Rootes combined Clément-Talbot and Sunbeam into Sunbeam-Talbot Ltd, which Rootes then sold to Humber Ltd, even though Rootes owned Humber… Still with me?

Anyway, Sunbeam-Talbot, now based in Clément-Talbot’s old Barlby Road, North Kensington, factory, debuted their 10 (previously a Talbot 10, previously a Hillman Aero Minx) and 3-Litre (basically a Hillman Hawk/Humber Snipe in a posh frock) at the 1938 Motor Show. The following year brought a Sunbeam-Talbot 2-Litre (a 10 with the Hillman 14 engine) and the 4-Litre (a 3-Litre with the Super Snipe engine). Unfortunately, that year also brought yet another scuffle amongst our continental friends, during which Sunbeam-Talbot production was halted entirely in favour of Karrier lorries.

In 1946, Rootes brought Sunbeam-Talbot out of the aging North Kensington plant and into the new family factory at Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry. The pre-war models returned, although materials were short and the big 3- and 4-Litre engine production mostly went to Humber, so the range was basically the 10 or the 2-Litre. It would be 1948 before Sunbeam-Talbot got some modern styling in the handsome, Packard-flavoured shapes of the 80 and 90 saloons or drophead coupes. Underneath, though, they were still the 10 and 2-Litre respectively, though the underpowered 80 was dropped in 1950, while the 90 MkII got a new chassis with independent front suspension and a larger 2.3 engine. Success in road rallies, especially a podium sweep in the 1952 Alpine Rally, led to a new model, a two-seat drophead coupe called the Alpine in 1953.

1962 Sunbeam Rapier Series III

1959 Sunbeam Alpine, raced by Bernard Unett (John Willshire)

1957 Sunbeam Rapier Series I (David Parrott)

In 1954, Rootes finally ended the previous confusion by dropping the Talbot name – all Sunbeams were now just Sunbeams, Rootes’ sports and performance brand. By 1956, the 90 and Alpine had been phased out, and the badge engineering stepped up a notch.

The 1955 London Motor Show saw the debut of the new Sunbeam Rapier, the first of Rootes ‘Audax’ family. A 1.4-litre, two-door hardtop coupe, it had been designed by the Loewy Studios, with transatlantic design cues from the contemporary Loewy-penned Studebakers, plus two-tone paint and column change. Its siblings – the Hillman Minx and Singer Gazelle – shared its underpinnings but debuted months later.

The Rapier Series II followed in early 1958, with the addition of a convertible, rear fins and a 1.5 engine. That was followed after just 18 months by the Series III, which looked very similar to the II but had an uprated aluminium cylinder head and front disc brakes from the Alpine.

Ah, yes, the new 1959 Alpine Series I, a handsome all-new two-seat sports convertible with styling from Loewy but underpinnings from the humble Hillman Husky. The Alpine was upgraded in 1960 with a new 1.6 engine and revised rear suspension to create the Series II, while the 1.6 engine was dropped into the 1961 Rapier to make the Series IIIA. The early Alpine had already been successful at Le Mans, and was popular with American circuit racers, but surely achieved most fame being driven around Jamaica by Sean Connery in Dr No, the first of the Bond franchise, in 1962.

To expand on the Alpine’s performance potential, Sunbeam investigated the possibility of equipping the Alpine with some American horsepower. In 1961, Ford had debuted a new, lightweight, small-block 221ci (3.6-litre) V8 engine, which soon grew to 260ci (4.3). Its compact dimensions just fitted the Alpine engine bay perfectly, and, with a little help from a certain chap called Carroll, who had experience in fitting American V8s into British sports cars, the Sunbeam Tiger debuted at the 1964 New York Motor Show. It was a roaring (literally) success on road and track, especially in America, and Rootes subcontracted the conversion work to Jensen.

Back in the real world, the 1963 Rapier Series IV was little changed. The Alpine had stolen much of its sporting cred, and Rootes were keener to go racing with the Tiger and the new Imp. The Series V Alpine and Series V Rapier both debuted in 1965, both featuring the new 1,725cc engine, but bigger changes were coming at boardroom level.

1964 Sunbeam Tiger engine bay (Greg Gjerdingen)

1965 Sunbeam Tiger (Steve Glover)

1971 Sunbeam Rapier

American giant, Chrysler, was keen to get a foothold in Europe and began buying up Rootes shares in 1964; by 1967, Chrysler owned Rootes. The latest Tiger had just upgraded to Ford’s 289ci (4.7-litre) V8, but Chrysler put the kibosh on the project – they’d be damned if they’d use rival Ford’s engines. The new Rootes Arrow range of cars was ready to take over from the old Audax cars in 1967, and the Sunbeam version was a handsome hardtop coupe called the Rapier Fastback. The following year, a higher-performance Rapier H120 came along with a Holbay-tuned version of the 1,725cc engine, just as the Alpine was phased out. A lower-spec version of the Rapier fastback, badged the Alpine, was introduced in 1970, at which point production of the fastbacks was moved to the Linwood plant.

Linwood, in Scotland, was one of the nails in the Rootes coffin. It had been specially built to produce the new-for-1963 Hillman Imp, Rootes’ late challenger to the Mini, but an under-developed product and industrial disputes had turned the place into an albatross. A performance Imp was badged Sunbeam Sport in 1966, with the Sunbeam Stiletto coupe following in 1967. To confuse matters further, most Rootes/Chrysler exports of all models in all ranges were soon badged as Sunbeams.

Singer, one of Sunbeam’s siblings at Rootes, had died in 1970, and, with Chrysler concentrating on more modern products coming from their other European concern, Simca, the British arm was left treading water in the turbulent Seventies. After introducing the Hillman Avenger in 1970, Chrysler showed little interest in the old Rootes brands, and the Sunbeam fastbacks struggled on until the Alpine was axed in 1975, the Rapier following in 1976.

The Sunbeam and Humber brands were quietly pensioned off together in 1976, never to be seen again, although, just to add some sprinkles to the trifle of confusion, the Imp’s replacement in 1977 was called the Chrysler Sunbeam. It got even better when, in 1979, Chrysler cut their (considerable) losses and got out of Europe, selling their whole European concern to PSA (Peugeot-Citroen) for $1. PSA instantly rebranded the whole Euro-Chrysler fleet as Talbots… so, 25 years after Sunbeam-Talbot finished, you could buy a Talbot Sunbeam.

Sunbeam Sport 1971

1975 Sunbeam Rapier

In 1981, PSA ended production of the Talbot Sunbeam at Linwood and closed the plant. They closed the ex-Rootes plant at Ryton-on-Dunsmore in 2006, it was demolished in 2007, and Network Rail now owns the site. The old Barlby Road, North Kensington, factory became a Rootes admin building after 1946, later becoming a Thames Television studio, and is probably best known as Sun Hill Police Station from ITV’s The Bill! It’s currently a photographic/film studio called Sunbeam Studios, with settings including the Talbot Hall and the Rootes Hall… At least the name lives on somewhere, because PSA have shown no signs of doing anything with Sunbeam other than leaving it to be quietly forgotten.