Hillman

Words: Dave Smith, images: as credited

A successful British marque for almost 70 years, this was another brand that died in the boardroom rather than the marketplace.

William Hillman was born in 1848 and apprenticed at John Penn’s engineering works. James Starley also worked at Penn’s, but left to move north and found the Coventry Sewing Machine Company with Josiah Turner in 1861. Starley headhunted promising engineers from down south, and William was among them.

The huge demand for sewing machines was slowing down at this point, but another seed was sown when James’ nephew, John Starley, brought his new bicycle into the factory in 1868. Figuring that they could improve on the design of the French boneshaker, James and William came up with a new penny-farthing design that they called the Ariel. James changed the company name to Coventry Machinists Co, and the Ariel was patented in 1870. With the Franco-Prussian war effectively halting French bicycle production that year, the company boomed.

In 1875, Hillman left to set up his own firm with WH Herbert, making their own bicycles, sewing machines and other goods. Hillman and Herbert were joined by George Cooper in 1880, and in 1884 they debuted the Kangaroo bicycle, still a penny-farthing but with chain drive. This use of chain drive led other manufacturers to refine and develop the system, leading directly to the ‘safety’ bicycle, the design we still use today. One of the pioneers of this design was none other than John Starley, whose new French bike had set the wheels in motion (a-ha-ha) almost 20 years previously. John’s revolutionary new Rover Safety Bicycle debuted in 1885, and his name went down in history as the inventor of the modern bicycle.

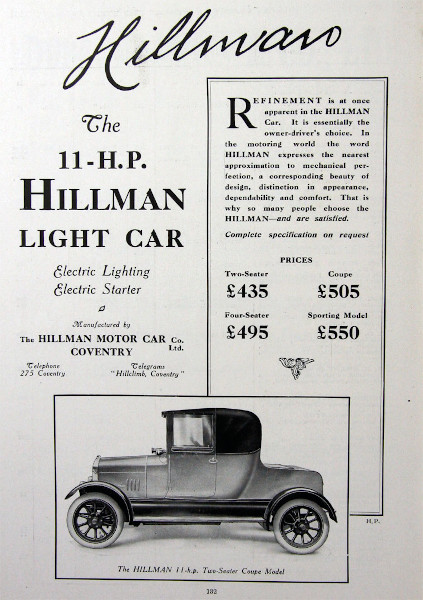

1920 Hillman advert.

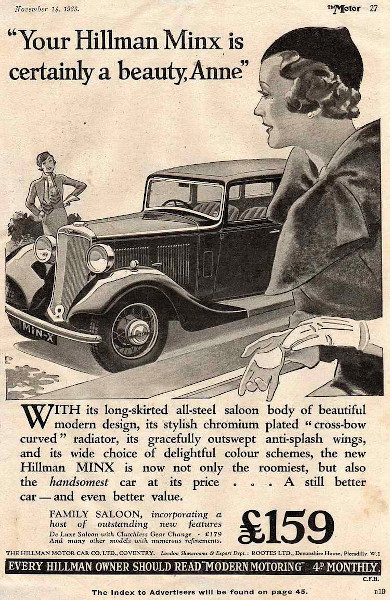

1933 Hillman advert.

1929 Hillman 14

Of course, John Starley’s Rover Safety Cycle Company eventually became Rover cars; his uncle, James Starley’s Coventry Machinists Co eventually became the Swift Motor Co.

But what of William Hillman? Radical new ‘safety cycles’ aside, Hillman, Herbert and Cooper were still doing very well with their penny-farthings and other engineering pursuits, and the company morphed into the Premier Cycle Co in 1891. They had several UK factories and one in Germany, and were selling their cycles as fast as they could produce them. Before the nineteenth century became the twentieth, Hillman was a millionaire.

Such wealth allowed Hillman to take interest in that expensive modern pursuit, motoring and motor racing, and decided that he wanted to build his own car. In 1905, he set up a factory in the grounds of his own house in Stoke Aldermoor, a suburb of Coventry, and drafted in Louis Coatalen, Humber’s brilliant chief engineer. The result was the 1907 Hillman-Coatalen racing car, which Coatalen himself drove in the new Isle Of Man Tourist Trophy Race. He crashed out, but had definitely attracted attention to the name.

In 1909, Coatalen left to join Sunbeam, so William re-named his firm the Hillman Motor Car Company in 1910. The first models he produced were huge machines with 6.4-litre four-cylinder or 9.7-litre six-cylinder engines, but these were made and sold in tiny numbers. Mass-market appeal came in 1913 with the 1.4-litre 9HP, soon followed by the six-cylinder 13/25, but then war in Europe threw a spanner in the works.

1934 Hillman Minx Sports Tourer

1935 Hillman Aero Minx (Andrew Bone)

1938 Hillman Minx (in period, with blackout headlamp)

When peacetime production resumed, the 9HP was upgraded to an 11HP with a 1.6-litre engine, and this, alongside its 10HP Sports sibling, was a reasonably popular model until the mid-Twenties.

Hillman had five daughters. The third, Dorothy, married Thomas Dick, chairman of Hillman’s Auto Machinery Co engineering company. The fourth, Margaret, married John Black, later Sir John Black, who had been on the board at Hillman since 1919. The youngest, Edith, married Spencer Wilks. When Hillman died in 1921, Black and Wilks became joint MDs of the company.

Under Black and Wilks, Hillman finally made their mark on the market with the 1925 Fourteen. It was a great seller, and was Hillman’s only model until 1928, when it was joined by the Straight Eight with an overhead-valve 2.6-litre engine. Unfortunately, engine reliability issues, coupled with the economic recession, condemned the Straight Eight to obscurity.

Before the Great War, one of Hillman’s Coventry neighbours, Singer, had employed a 15-year-old boy named Billy Rootes as an apprentice. Young Billy left Singer in 1913 to start his own car dealership, perhaps little knowing that he would later become Sir William, later still 1st Baron Rootes, and a captain of industry who ended up owning the company at which he apprenticed.

William Rootes and his brother, Reginald, had a mighty empire of dealerships in the Twenties and, with an eye to a burgeoning export market, they sought a foot in the door of being manufacturers as well as middle-men. They set their sights on Hillman and next door neighbour Humber and, by 1928, had bought enough shares to have a controlling interest in both. They engineered a merger that made Hillman a subsidiary of Humber.

When Rootes Brothers took over, both Wilks and Black left the Hillman board. Wilks went off to be Works Manager at Rover, later becoming MD, Chairman, then President. He also founded Land Rover. Black went to the board of Standard, later Standard-Triumph, and stayed until being forced to retire due to ill health in 1954. He was succeeded as MD by his long-time right-hand man, Alick Dick, nephew of his brother-in-law, Thomas…

1939 Hillman 14

1944 Hillman RAF Staff Car (Montrose Museum, Kevan Dickin)

1954 Hillman Husky MkI (Kieran Turner)

1957 Hillman Minx advert.

The canny Rootes Brothers expanded their empire by picking off marques injured by the recession. They quickly brought Commer into the Humber fold, later adding Karrier, Sunbeam, Clement-Talbot and, much later, Singer to the list.

Back to Hillman, where, as the Thirties dawned, there was only the popular Fourteen model and the white elephant Straight Eight, the latter becoming the Vortic in 1930, which didn’t help. Rootes set about rationalising their ranges – why have Hillmans that competed with Humbers? In 1931, the ageing Fourteen was replaced by the Hillman Wizard 65; the Vortic by the Wizard 75, a large step down. Both had new but conventional side-valve six-cylinder engines, but neither was a roaring success.

The next new model was an immediate winner and became a household name for the next 40 years – the 1931 Hillman Minx. Handsome, compact and affordable, the 1.2-litre Minx cemented Hillman’s position in the Rootes group as purveyors of quality, smaller cars. Throughout the Thirties, the six-cylinder Hillmans fell by the wayside until only the Minx remained. At the 1937 Olympia Motor Show, its larger sibling, the new Hillman Fourteen, was unveiled, and the last of the big six-pot Hillmans – the Hawk – appeared on the Humber stand badged as the new Snipe. With Humber as the luxury brand, and Sunbeam filling the sporting niche, Hillman was free to make the small- and mid-range market its own. Thus, Rootes rationalised the range.

Unfortunately, this was the time at which Herr Hitler was making his feelings known across Europe, and car production would have to wait. Although Hillman did build Minx saloons for the military and Minx-based ‘Tilly’ pick-ups, their main business became aero engines and, later, aircraft. The Rootes brothers must have had an idea of how much attention the Luftwaffe would pay Coventry, because it was their work with the Shadow Factories scheme, and subsequent assistance in rebuilding a shattered Coventry, that earned them their titles. The Shadow Factories scheme saw Rootes build their huge new assembly plant in Ryton-on-Dunsmore, where they’d stay until the end. They weren’t infallible, though. After the war, Sir William Rootes was offered Volkswagen’s Wolfsburg factory and the new Beetle as part of war reparations. He turned it down, thinking that it would never sell. The Beetle was sold for 65 years, with over 21million produced. Whoops.

1957 Hillman Minx Convertible

1955 Hillman Minx Californian

1961 Hillman Husky

1963 Hillman Super Minx convertible (Andrew Bone)

After the war, the Minx picked up exactly where it had left off, the only Hillman model available. The Rootes Group was too busy chasing the export dollar, and in the years immediately following wartime, opened new factories in key markets overseas and new distribution networks in America, Canada, Brazil, and more.

The Minx MkII, or Phase II, came along in 1947 with styling halfway between the pre-war separate wings and modern integrated wings. The 1948 Phase III completed the transition, with a rounded body and full-width horizontal grille. In 1949, the Phase IV bored the 18-year-old 1,185cc side-valve engine out to 1,265cc, helping the Minx accelerate from 0-60mph in a shade under 40 seconds.

The 1951 Phase V began to get a little extra American-style chrome, while the 1953 Phase VI took the transatlantic theme a step further with the addition of a pillarless two-door hardtop coupe, the Minx Californian. The Phase VII was not much changed, but the 1954 Phase VIII gave the Minx a new, 1,390cc overhead-valve engine. Another debut in 1954 was the Hillman Husky, a budget three-door estate based on a shortened Phase VIII floorpan but still with the old 1,265cc side-valve.

Behind the scenes, Rootes were busy on the all-new models, and had taken their transatlantic look a huge leap forward with assistance from American designer and stylist, Raymond Loewy. Loewy had just finished turning Studebaker’s range from dowdy and dull into cutting-edge, iconic, jet-age masterpieces. He was hot stuff.

The new range, codenamed Audax, debuted in the spring of 1956 with the Minx Series I. With its chrome grille, canted pillars and a wraparound rear screen, it was very contemporary (with more than a whiff of Studebaker about it). Another trick borrowed from America was the annual model change. The Series II came along in 1957, the Series III in 1958, the Series IIIA in 1959, the Series IIIB in 1960, the Series IIIC in 1961, the Series V in 1963 and Series VI in 1965. Nobody knows what happened to the Series IV.

The engine grew with the models, too. The I and II had the old 1,390cc, growing to 1,494cc in the Series III and to 1,725cc in the VI. The range itself grew with the 1961 addition of the Super Minx, a larger sibling in saloon, estate and short-lived convertible forms. Rootes Group was keen on badge-engineering, so there were Sunbeam Rapier and Singer Gazelle versions of the Audax Minx body, and Singer Vogue and Humber Sceptre versions of the Super Minx.

The early part of the Swinging Sixties would seem to have been a swinging time for the Rootes Group, with its handsome new models and global presence, but there was trouble waiting in the wings. First, there was constant industrial action at British Light Steel Pressings Ltd, a Rootes company that pressed car panels. Starting in 1959, workers at the Acton plant would strike over any issue, no matter how trivial. In the first eight months of 1961, there were 82 walkouts, mostly unofficial and against union advice. This slowed production lines to a crawl, causing thousands of Coventry workers to be laid off, and put Rootes Group well into the red.

The next nail in the coffin was named the Imp. Everyone had been caught out by the runaway popularity of the Mini from rivals BMC, and Hillman’s answer was the little Imp, with its rear-mounted, all-aluminium 875cc engine. On paper, it was a terrific little city car, but its first problem was that it was four years too late, and would never escape the Mini’s shadow. The second and larger problem was that the government “persuaded” Rootes into building the Imp in a new factory in Linwood, west of Glasgow, an area of high unemployment. The factory was built in 1961, and Imps began rolling out in 1963. Shipping cars and components between Coventry and Linwood proved costly, build quality and reliability proved elusive, and, after a positive start, sales soon tailed off and both the Imp and the Linwood factory proved to be an albatross for Rootes.

1966 Hillman Imp

1967 Hillman Super Minx Estate

1970 Hillman Avenger GL

At about the same time, Chrysler, the third of America’s ‘Big Three’ car manufacturers, was looking for a foothold in Europe, and began buying Rootes shares and installing its own men on the board; however, Rootes was busy with the 1966 Arrow range. Completely new, it replaced the dated American fins’n’chrome styling of the Audax and Super Minx range with modern, crisp lines. First out of the gate was the Hillman Hunter in October 1966, with the 1,725cc engine, followed six months later by a lower-spec 1,496cc budget version badged the Hillman Minx.

In early 1967, Chrysler increased their shareholding to almost 80%, and a takeover became inevitable. Lord Rootes had died just before Christmas, 1964, and his brother, Sir Reginald, who took his place as Chairman, stepped down in March 1967.

The first car developed by the new British arm of Chrysler was the Hillman Avenger, which debuted in 1970 and replaced the Minx version of the Arrow. It had handsome styling, new powertrains and nimble handling, and Chrysler even tried to sell it in the USA as the Plymouth Cricket. Sadly, it wasn’t a success and they withdrew it from the market just before the 1973 OPEC-engineered oil crisis that saw American demand for small cars soar…

Under Chrysler, old Rootes names began to fall away – first Singer in 1970, then Sunbeam, then Humber in 1976. Finally the Avenger and Hunter were both badged as Chryslers in 1976, the Imp was killed off, and the Hillman name disappeared.

1970s Hillman Avengers were exported to Europe badged as Sunbeams

1976 Hillman Avenger

Serious financial difficulties at home meant that the giant Chrysler was in dire straits and looked to cut the troublesome Chrysler Europe loose. In 1978, they sold the lot to Peugeot for $1. The first dead wood that Peugeot cleared was the Chrysler Hunter; the next was the Linwood plant. Talbots, and subsequently Peugeots were built at the Ryton-on-Dunsmore plant until 2006; it was demolished in 2007. Strictly speaking, Groupe PSA, still owns Hillman. A renaissance is highly unlikely…