Rover

Words: Dave Smith, photography: as credited

From Edwardian grandeur, through the corporate wilderness of the Seventies, to the ignominy of death and dissection. Such is the fate of Britain’s last volume car manufacturer.

The two cities of Birmingham and Coventry could be considered the British equivalent of Detroit, the Motor City. One company that was born – and lived – at either end of that stretch of A45 was arguably its best-known and longest-lived: Rover.

It all began when the bicycle was king. James Starley was well known for making sewing machines but, in 1869, made the transfer into the bicycle trade. One of his employees was his nephew, John K Starley, who left his uncle’s company, joined forces with William Sutton and founded Starley & Sutton Co in Coventry in 1878. The first vehicle to carry the Rover name was a tricycle, launched in 1883.

Back then, tricycles and penny-farthing-style high-wheelers ruled the cycling world. John Starley thoroughly upset that world when, in 1885, he introduced the new Rover Safety Cycle, a bicycle with a diamond-shaped frame, two wheels the same size, and a chain-drive to the rear. A contemporary cycling magazine suggested that this new model had “set the pattern to the world,” and they were right. More than 130 years later, the world is still pedalling machines that resemble Starley’s first Rover.

By 1889, William Sutton left the company, and John renamed it JK Starley & Co Ltd. Late in the 1890s, he rebranded again to The Rover Cycle Company Ltd, then began importing Peugeot engines and experimented with fitting them to bicycle frames. Sadly, this would be the last contribution from the man who had revolutionised the world of cycling. John Starley died in October 1901, at the age of just 46.

The Rover Cycle Company Ltd was taken over by Harry J Lawson, a bicycle designer and racer (whose designs ran parallel to Starley’s and often overlapped). Lawson was also something of an entrepreneur in the nascent automobile industry, with his fingers in many motor manufacturing pies, including the early Daimler concern, so it was natural that he’d continue Starley’s work. This led to the Rover Imperial motorcycle, which launched in late 1902, and the Rover brand would continue to build motorcycles into the Twenties.

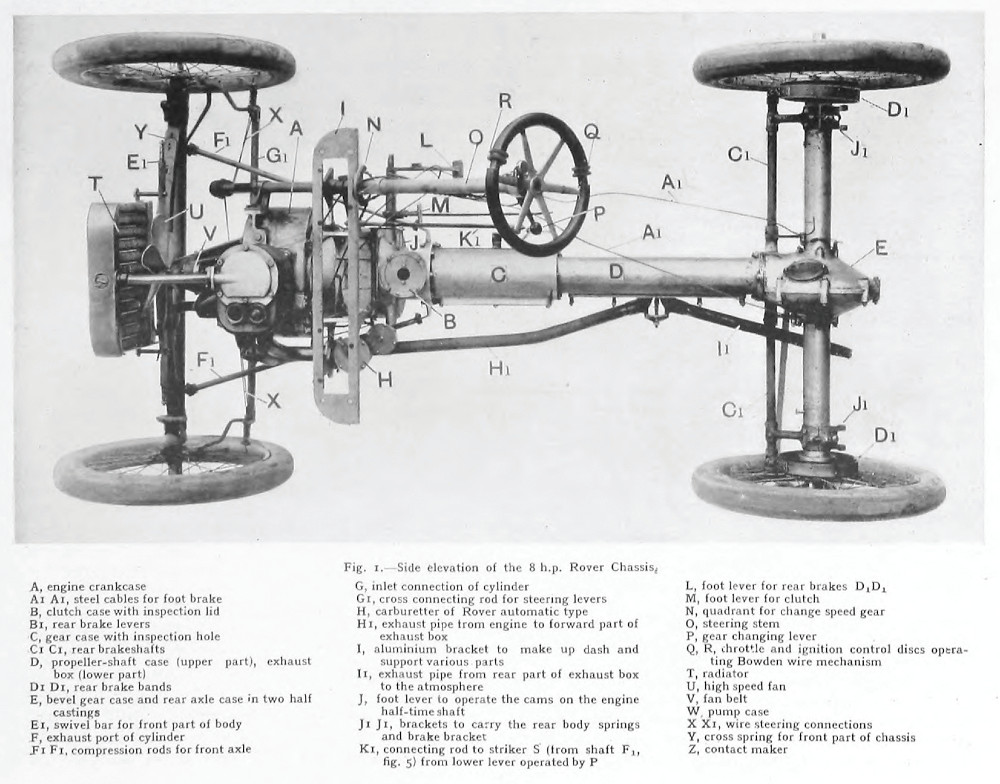

Flushed with this success, Lawson brought designer Edmund Lewis over from Daimler, to work on Rover’s first automobile. The fruit of this labour would be the 1904 Rover Eight, a single-cylinder, 8hp two-seater with the world’s first backbone chassis.

All was not well in the boardroom, however, and some of the pies Lawson had his fingers in, which had been under legal scrutiny since the turn of the century, came back to hit him in the face. He landed himself in court for defrauding shareholders, subsequently ending up on the busy end of a year’s hard labour.

In the meantime, back at Rover’s Coventry plant, there was a smaller, cheaper 6hp car to come in 1905, built on a more conventional chassis but with an early effort at rack and pinion steering, shortly followed by four-cylinder 10/12 and 16/20hp models.

It was after these models debuted that Lewis left to join Deasy, and Rover found themselves fumbling with new designs, including a brief affair with the Knight sleeve-valve engine, before hiring a new designer, Owen Clegg, from Wolseley in 1910. Clegg’s first designs were the 2.3-litre 12hp and 3.3-litre 18hp models, which were unveiled in 1912, and proved so successful that Rover dropped all other models, until the summer of 1914 when war took priority. During those dark days, Rover were kept busy supplying motorcycles to the British and Russian armies, plus building Maudslay trucks and Sunbeam-based ambulances.

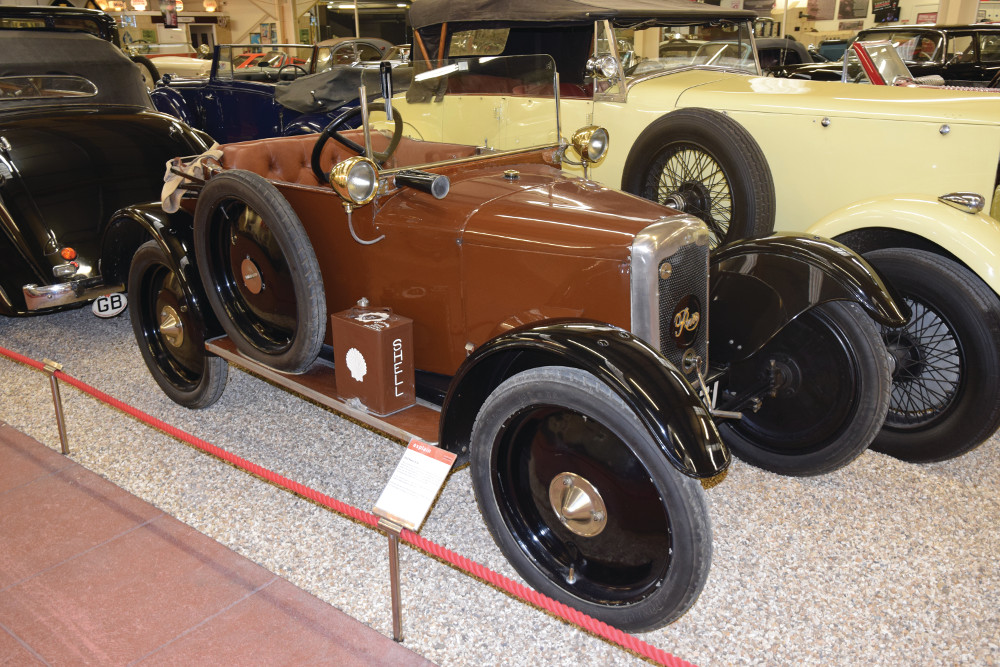

Once hostilities ceased, the same range went back on the market, though the 12 was upgraded to a 14. Clegg had left to join Darracq before the war, so Rover bought a design for a small, 8hp car from Jack Sangster at Ariel motorcycles, and set up production in a new factory in Birmingham. The Rover Eight had an air-cooled flat-twin engine and was sturdy, reliable and cheap. It was a decent seller until some Herbert from Longbridge brought out the Austin Seven in 1922.

Having seen the writing on that particular wall, Rover began to move upmarket with the 1924 Nine, followed by the 14/45 with its interesting new overhead-cam engine. As interesting as the new engine was, it was completely overmatched by the heavy 14/45, so was upgraded to the 16/50 with a more powerful engine.

Times were tough, though, and Rover suffered. In 1928, the Nine was replaced with the unremarkable 10/25, along with a new six-cylinder, two-litre, overhead-valve model, but the company was heading for insolvency. Later that year, the board appointed Frank Searle as Managing Director with instructions to save Rover.

1922 Rover 8 (Hugh Llewellyn, at Haynes Museum)

1926 Rover 9

Searle immediately brought in Spencer Wilks, William Hillman’s son-in-law, who had just left Hillman after the Rootes brothers takeover, and gave him the title of General Works Manager and a seat on the Rover board. Wilks’ first move was to divest the Midland Light Car Bodies subsidiary, then bring in two new designers, Robert Boyle and Maurice Wilks. Maurice was Spencer’s younger brother, just back from a brief stint with General Motors in Detroit.

Boyle and Wilks Jr were tasked with designing a new small car, and the result, the rear-engined Scarab, was even displayed at the 1931 London Motor Show, but never saw production. Rather more significant was another 1931 debut, named the Pilot, also designed by Boyle and Wilks Jr, with a small six and a freewheel transmission…

Searle and Wilks Sr had abandoned the bargain-basement Scarab and wanted to move the Rover brand further upmarket. After a couple of years of heavy losses, but with black ink on the horizon, Searle vacated his seat on the board, leaving Spencer as MD and putting Maurice in charge of engineering and design. This led to the Rover 10 P1 of 1933, with its brand-new 1.4-litre engine, freewheel transmission and underslung chassis. It was a handsome beast, and, costing around 50% more than the competition from Longbridge or Cowley, showed exactly which market Rover was aiming for.

The 10 was followed by a 12, and a six-cylinder 14 directly descended from the Pilot show car. The 14 soon begat a 16, then a 20, while production – and profits – soared. Rover took part in a government ‘shadow factory’ scheme, and opened new plants in Solihull and Acocks Green, a suburb south of Birmingham. The latter was running when the Rover 10 P2 was launched in 1939, but, of course, another continental fracas put a spanner in the works that year.

1928 Rover 10 Tourer (Clive Barker)

Rover P1 12 Tourer (1936)

The Coventry, Solihull and Acocks Green sites were put to work making aircraft engines and airframes. The benefits of the shadow factory scheme soon became painfully obvious, as the Luftwaffe bombed the Coventry factory so heavily during 1940 and ’41 that it was never fully rebuilt or returned to full production.

In 1940, Rover were approached by Frank Whittle to produce his new jet engine. Maurice Wilks helped refine Whittle’s design, and they built the first test engines in a Lancashire mill building, but soon, after clashing with Whittle over the design, and being slightly out of their depth with the production, Rover did a deal with Rolls-Royce. Rover handed over the whole jet engine show to Rolls, and Rolls gave Rover the tooling, contract and Nottingham factory that built the Meteor V12 tank engine. Incidentally, while Rolls built Whittle’s jet engine and named it the Welland, their new and improved engine was based upon Rover’s improvements to the Whittle unit, and became the Rolls-Royce Derwent.

A great deal changed after the war. Rover abandoned the damaged Coventry factory, moving all their automotive concerns to Solihull, while the Acocks Green plant continued to make Meteor engines. The P2 resumed production at Solihull, but would be short lived; the P3 – the four-cylinder 1.6-litre 60 and the six-cylinder 2.1-litre 75, both with new chassis, independent front suspension, hydro-mechanical brakes, debuted early in 1948.

Another debut for that year was a complete departure from the handsome, comfortable and upmarket Rovers. Maurice had an army surplus Willys Jeep for trundling around his farm, but he and Spencer thought they could do better. The result was the first Land Rover, which went on show in 1948. Land Rover went on to be a spin-off from Rover and, eventually, more profitable and long-lived than the parent.

Incidentally, at the time of the Land Rover’s introduction, there was a new employee at Rover, fresh from his apprenticeship at Rolls-Royce. His name was Charles Spencer King, better known as Spen, the Wilks brothers’ nephew, who would go on to develop, among many other things, the Range Rover.

Meanwhile, back in the world of comfortable passenger cars, the 1949 Motor Show witnessed yet another new machine from Rover. The Gordon Bashford-designed P4 75 was middle-sized, modern and handsome yet conservative with a solid, dignified air. The 75’s only avant-garde feature was a central front fog lamp, a styling cue possibly borrowed from the contemporary Loewy-designed Studebakers, which led to the first 75s being nicknamed the Cyclops. They were so very British it brought a tremble to even the stiffest upper lip, and so well loved that the P4 became affectionately known as the Auntie Rover.

The six-cylinder 75 was later joined by the four-cylinder 60 and more powerful six-cylinder 90 in 1953, and the high-performance 105S (manual) and 105R (auto, using the charmingly-named ‘Roverdrive’ two-speed-plus-overdrive ‘box) in 1956. Towards the end of the Fifties, the 60 was replaced by the 80, and the 90 and 105 replaced by the 100; in the early Sixties, the 95 replaced the 90 and the 110 replaced the 100. Pick a number, any number.

While the P4 range was the very epitome of conservative middle-class, there was a Wild Rover in the family. Maurice Wilks had not forgotten all he’d learned with Whittle, and brought in Frank Bell and the aforementioned Spen King to help him develop a gas turbine engine for the road. The prototype, JET1, based on a roofless roadster version of the new P4 75, was unveiled to shock and awe in early 1950. It later went on to run at 150mph, spawned various other prototypes, and even a joint project with BRM to build a gas turbine racing car to compete at Le Mans. It’s a tale that demands a whole book to itself, but, sadly, despite all this, it seems that gas turbine research didn’t amount to much back in Solihull, and was not pursued much further.

1949 Rover P3 75

1950 Rover JET1 (Jonathan Cardy)

Rover P4 90 (1954)

Back in Rover’s day-to-day world, things were looking rosy and, in the autumn of 1958, the new P5 launched. This was a large executive four-door saloon, styled by David Bache, longer and wider than the P4, and lazily comfortable thanks to the three-litre inlet-over-exhaust straight six. A MkII version came along in 1962 with more power, and a very stylish four-door coupe version with a lowered roofline. The 1965 MkIII was more powerful again, but then came the tour de force, the 1967 P5B with the new aluminium V8 engine bought from General Motors. The P5B could be staid establishment and hooligan at the same time; a car loved by both bank managers and the men who robbed them.

Spencer Wilks retired in 1962, at the age of 70, though he kept a position as a non-executive director and would later be President of Rover. Maurice Wilks succeeded his brother as chairman, and WFF Martin-Hurst (Maurice’s brother-in-law) got the managing director gig while Peter Wilks (Maurice and Spencer’s nephew) took over as technical director. Just a year later, in 1963, Maurice died at the age of 59; Spencer saw his 80th and last year in 1971.

Maurice died just a month shy of seeing the company’s groundbreaking new baby debut at the October 1963 Earl’s Court Motor Show. It was the Rover P6, the work of King, Bashford and Bache, and was aimed at the younger executive who was too dynamic for the big P4 or P5 but wanted something classier than a Zephyr. Styling was crisp, clean and modern, but not flashy, and that skin concealed such modern tech as bell-crank front suspension, De Dion independent rear suspension, all-round disc brakes and a new OHC two-litre, four-cylinder engine. It was a hit, and the P6 was named the first ever winner of a new award: European Car Of The Year, in 1964. Things got even better in 1968 when the P5B’s 3.5-litre V8 was dropped into the spacious P6 engine bay.

At the same time, the Rover board’s traditional keep-it-in-the-family approach was about to experience a major upset. It began when the Leyland Motor Corporation, who had owned Standard-Triumph since 1960, bought Rover and Land Rover in 1967. Meanwhile, the British Motor Corporation had spent the Fifties conglomerating Austin, Morris, MG, Riley and Wolseley, before finally merging with Jaguar in 1966 to create British Motor Holdings Ltd. In May 1968, under pressure from on high in the Wilson government, Leyland and BMH merged to form the British Leyland Motor Corporation.

1965 Rover P6 2000 (Heritage Motor Museum)

1965 Rover-BRM Le Mans Gas Turbine car (British Motor Museum)

1968 Rover P6 2000TC

There was a definite two-tier system in the new British Leyland. The BMC marques shared everything, to the extent that the ADO16 1100/1300 saloon was an almost identical car marketed under five different brands; six if you counted Vanden Plas. The upper echelon ‘Specialist Division’ marques, however, were fiercely independent and secretive. The Rover P6’s biggest market rival had always been the Triumph 2000, and they were still competing even though they now lived under the same roof. Rumour has it that Jaguar had deliberately designed their new XJ6’s engine bay to be too narrow for the Rover V8, for fear that BL brass would take away their beloved DOHC straight six and foist the V8 upon them.

In 1973, the P5B was discontinued and the P6, while still popular, had reached its 10th birthday, so the dream team of Bashford, King and Bache were tasked with creating a jaw-dropper. The trio, whose last hit was the 1970 Range Rover, clearly had a poster of a Ferrari 365GTB/4 pinned up in the studio, because what came out was a stunner – the SD1, a swoopy, modern five-door hatchback powered by the old faithful V8, that debuted in 1976.

It was, however, born under a very bad star. BL bean counters had been busy restructuring and chucking the dead wood overboard – Riley had gone in 1969, Wolseley was going – but the monstrous corporate hull was sinking fast. It had become a Seventies poster child for inefficiency, internal political and industrial unrest, poor planning and patchy quality control, and, in early 1975, went spectacularly bankrupt. It was salvaged into British Leyland Limited, and effectively nationalised by the Wilson government.

Amazingly, the new Rover survived and thrived, taking the title of European Car Of The Year 1977. At the end of that year, the 2300 and 2600 models were released, using heavily redesigned OHC versions of the old Triumph straight-six, which meant that the now-15-year-old rivals, the Rover P6 and Triumph 2000/2500, could finally be pensioned off.

1970 Rover P5B saloon

1977 Rover P6 3500 (Allen Watkin)

1977 Rover SD1 (Paul Brown)

More corporate restructuring in ’77 meant that the new BL Cars Ltd was now split into three groups: Austin-Morris, which included MG, and JRT, for Jaguar-Rover-Triumph. Third was the Land Rover Group. At the dawn of the Eighties, the SD1 range was facelifted, and had expanded to encompass a 2.4-litre VM turbo-diesel, and a base-model using the Austin-Morris 2.0 O-series engine, though this was overmatched by the bulky SD1.

Little did they know that the SD1 would be the last ‘proper’ Rover. BL CEO, Michael Edwardes, had seen BLMC heading for the plughole while Japanese imports commanded an ever-increasing share of the market, so, for the future of BL, he looked east. He began working more closely with Honda, the first child born of this union being the short-lived Triumph Acclaim. As the old names – Morris and Triumph – fell by the wayside, so the Honda content of the recently streamlined Austin-Rover grew, while Jaguar was spun off and privatised in 1984. By the time the Maestro and Montego were being phased out, Austin-Rover had become the Rover Group. Who’d have guessed that Rover would be the sole surviving name in the fiasco that had been British Leyland? It was privatised in 1988, sold to British Aerospace, though by that point, everything coming out of Longbridge or Cowley seemed more Honda than not.

The SD1’s replacement, the front-wheel-drive 1986 Rover 800 series, was based on Honda’s Legend, using either a 16-valve version of the old O-series four-pot or a Honda V6. Then the old Rover 200 – beloved of Hyacinth Bucket and itself based on the Honda Ballade – was replaced by the new Concerto-based 200 and 400 series between late 1989 and early 1990. This was powered by the revolutionary new Rover K-series DOHC 16v, which won awards for engineering on launch, but will only be remembered for its rapacious appetite for head gaskets. Then, in 1993, the Accord-based 600 series showed up. It was tragic that this very British marque had all but turned Japanese, but Honda was probably the saving of Rover.

At about this time, BMW came knocking and bought the whole show, eventually splitting it all up in 2000, selling Land Rover to Ford, keeping the Mini brand for themselves, and selling MG and the rights to use the Rover name to the Phoenix consortium. Phoenix was an appropriate name, as their new MG Rover group had to bring the struggling brand back from near death. Much restructuring followed. The Metro/Rover 100 series and the 600 series were discontinued. The 200 series was renamed the 25, the 400 the 45, and the 800 was replaced with the rather handsome new 75 four-door saloon.

MG Rover under Phoenix first introduced a Tourer estate version of the 75, followed by sportified MG versions of the Rover range. When the Rover 75 V8 and the ZT or ZT-T 260 joined them in 2002, using Ford’s Modular 4.6 V8 engine and rear-wheel drive, they’d created a proper, understated British sleeper.

Sadly, none of this would amount to much. Sales were on the slide thanks to the 25 and 45 still being essentially Eighties Hondas under the skin, and the blind alley that was the woeful CityRover, a rebadged Tata Indica. MG Rover had never turned a profit, and amid rumours of buyouts, sell-outs, takeovers and even government intervention, the production lines stopped in April 2005.

1997 Rover 216 Coupe

2005 Rover 75 V8 Connoisseur

Then the scramble began, with Nanjing Automobile and the Shanghai Automobile Industry Corporation fighting over the corpse. Nanjing ended up with MG, and wanted the rights to Rover, but BMW had promised first refusal to Ford back during the Land Rover sale. SAIC ended up buying Nanjing in 2007, and they now make MGs. When Ford sold the whole Jaguar Land Rover concern to Tata Motors in 2008, they bundled Rover rights in with the deal; Tata haven’t done anything with those rights, so far.

So, the last British volume car manufacturer is now owned by an Indian company and only exists on paper in a filing cabinet in Mumbai. Will the longship badge ever reappear on an upmarket executive saloon? Or, worse, will it be used as the MG badge has been, to reflect some decades-old faded glory onto a range of unremarkable hatchbacks and SUVs? Obscurity or ignominy – which would be worse?