Standard

Words: Dave Smith, photography: various, as credited

Standard did indeed set the standard across the Empire/Commonwealth, but couldn’t survive the Swinging Sixties.

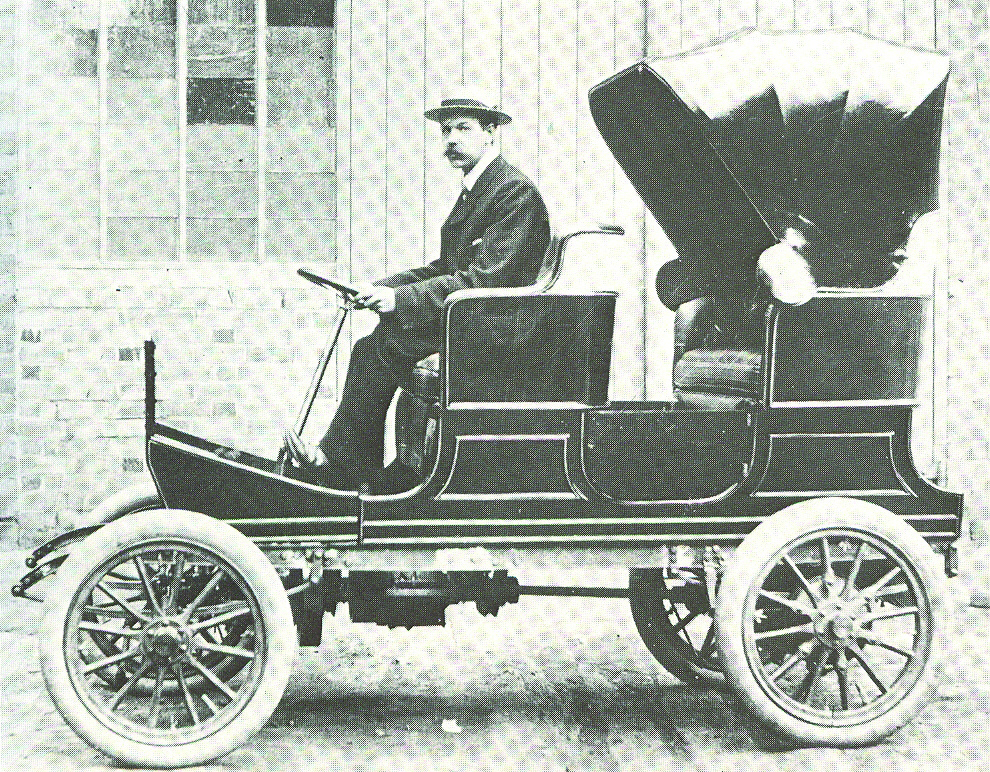

1903 Standard 6hp

1910 Standard 30hp Model G (Clive Barker)

Students of Industrial Revolution-era history may well be familiar with the name Henry Maudslay. Amongst his many achievements, probably the most significant was his screw-cutting lathe, which he built as the eighteenth century turned into the nineteenth, and which cut standardised, repeatable threads into bolts and nuts. Prior to that, most bolts and screws had hand-cut threads, so no two were exactly the same – can you imagine…?

It seems that engineering talent ran in the Maudslay family blood. Henry’s sons followed him into the engineering field, and, as the nineteenth century became the twentieth, old Henry would doubtless have been delighted to know that his great-grandson, Reginald Walter Maudslay, was an accomplished civil engineer, working under Sir John Wolf-Barry. Sir John was best known for London’s Tower Bridge, though this was completed before Reginald joined the firm.

Reginald would not stay long in the civil engineering field. The most exciting game in town was the internal combustion engine and, as Victorian became Edwardian, Reginald joined his cousin Cyril at the Maudslay Motor Works in Coventry, building marine engines. This wasn’t a successful venture, but they began looking into building engines for those new-fangled cars, and, by the end of 1902, they’d built an Alexander Craig-designed engine and fitted it to a car chassis.

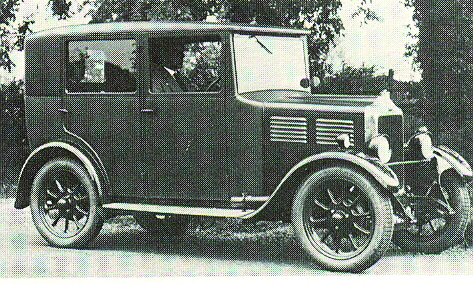

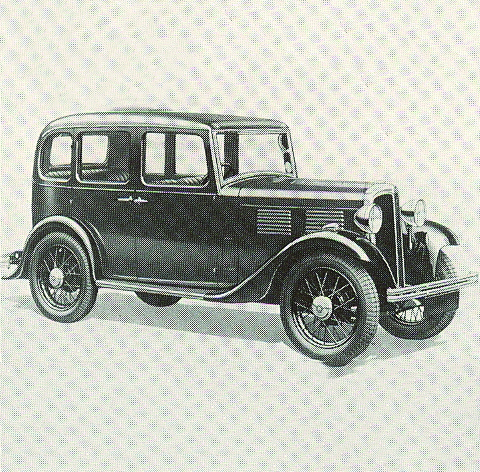

1928 Standard 9hp Fulham

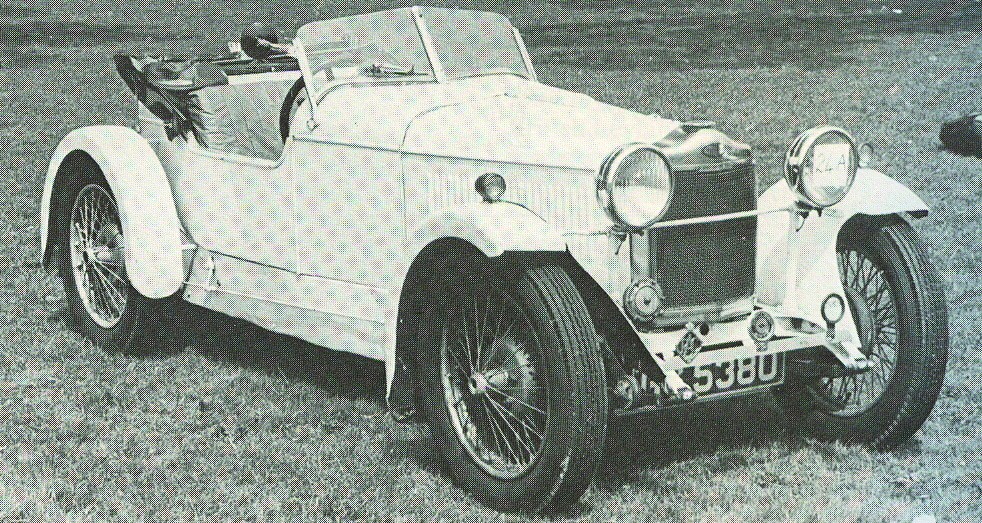

1930 Standard 9hp Avon Special

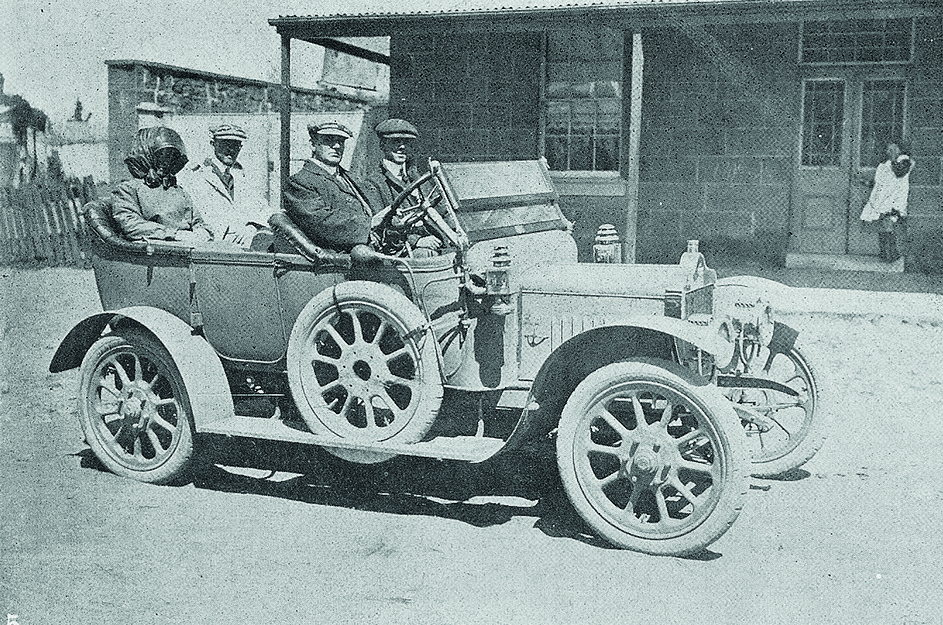

1911 Standard Eleven in Tasmania

1922 Standard Eleven in Dutch museum (Alf Van Beem)

That was the catalyst. Reginald realised where the future lay, and, with a gift of £3,000 (over £350,000 today) from Sir Wolf-Barry, he left to set up on his own. In March 1903, the Standard Motor Company was incorporated, with a small factory on Much Park Street, Coventry, and seven employees.

The first car to come out of the Standard works that year was a 6hp, single-cylinder, shaft-drive machine. Two more were built before Maudslay took on another 18 workers and increased production sixfold for 1904. The single-cylinder car was replaced by a two-cylinder, followed by a three, then a 16hp four-cylinder in quick succession.

In 1905, the Standard Motor Company exhibited at the London Motor Show, where Maudslay met a London car dealer, Charles Friswell, who was so impressed that he signed an exclusive contract for all Standard’s factory output.

Standard moved to larger premises, and, after a brief flirtation with air-cooled engines, concentrated on the six-cylinder models, including a monster 12-litre, 50hp machine. Friswell joined the board, becoming company chairman in 1907. Standard was going great guns, with the four-cylinder volume models selling well, and the six-cylinder models raking in the profits, but, in 1911, Friswell’s own company’s financial problems began to drag Standard down. By the end of the summer of 1912, Standard workers were on short hours, and Friswell’s sole dealership contract was terminated. He sold his Standard interests to Charles J Band and Siegfried Bettman, the latter being the founder of Triumph Motorcycles and, later, the Triumph Motor Company, which would eventually become an important part of Standard’s future.

Standard weathered this storm, and soon released their first commercial vehicle and the new, affordable four-cylinder 9.5hp Model S, which came with a three-year warranty. Standard became a public company in 1914, and were about to move production to their new Canley factory when the Kaiser disrupted their plans. Instead of new cars, workers were building aeroplanes, shells and mortars. More than 1,000 aircraft left the Canley plant between 1916 and 1918.

Civilian production resumed at Canley in 1919 with a facelifted Model S, and the post-war boom saw them selling all the ‘light cars’ they could make. By 1924, they were turning out 10,000 cars a year, a similar number to Austin. The good times couldn’t last, though, and as the boom faded and other manufacturers fell by the wayside, Standard struggled to keep its head above water. The crunch came in 1927 when Maudslay used the promise of a huge upcoming export contract to Australia to heavily reinvest in the factory. Unfortunately, the contract fell through, leaving Standard in the red.

As the market for the larger models fizzled out, Standard was left clinging to just one bargain-basement car: the fabric-bodied 9hp Fulham. By this time, Maudslay’s engineering skills were looking somewhat outdated, and he was bringing in outside assistance. One such recruit was John Black, from nearby Hillman, brought in to help turn the tide. This he certainly did, one of his earliest ideas being to concentrate on supplying chassis to external coachbuilders such as Jensen and Swallow.

1933 Standard Little Nine

1934 Standard Ten

1939 Standard Flying Eight

1940, a WAAF cranks a Standard 5cwt ‘Tilly’

Black took his seat on the board as joint MD alongside Maudslay, and, with the new Big Nine, Big Twelve four-cylinders, and new Ensign and Envoy six-cylinders, the Thirties began in strong form. Maudslay resigned in 1934, and Charles Band took over as chairman. Maudslay didn’t get to enjoy his retirement, though; he died just a few months later, on December 14th, 1934.

The new Standard Nine and Ten bolstered the lower end of the range and, at the 1935 Motor Show, the new, streamlined Flying Standards were unveiled. As all production was finally moved into the Canley factory, the 1936 Flying Standards, with their new waterfall-style grille and sloping rear end, all but replaced the old models. From the four-cylinder Flying Nine to the six-cylinder Flying Twenty, they were a handsome range of cars, although the Flying V-Eight, with a flathead V8 engine, didn’t sell as well as hoped. In 1938, a new satellite factory was opened at Fletchampstead, and the little four-cylinder Flying Eight was introduced, the first British mass-produced light car with independent front suspension. By the end of that year, Standard were selling 50,000 cars a year.

There was another new factory opening, too. With the threat of war once again blowing in from the continent, a new plant on Banner Lane was being built under the government’s ‘shadow factory’ scheme. After Churchill declared war, Standard produced Tillys (cars with utility bodies) at Canley, and aero engines at Banner Lane, along with de Havilland Mosquito aircraft and other military machinery.

When peace finally returned after seven long years, the pre-war Eight and Twelve were hurried back into production, but there were many other great changes afoot. The company leased the Banner Lane site from the government and joined forces with Harry Ferguson to make tractors, a successful venture that helped to fund R&D at Standard. Then Sir John Black – he was knighted in 1943 – negotiated the purchase of Triumph Motor Company, which had gone under in 1939, from the receivers for £75,000 (about £3.2 million today), making it a Standard subsidiary.

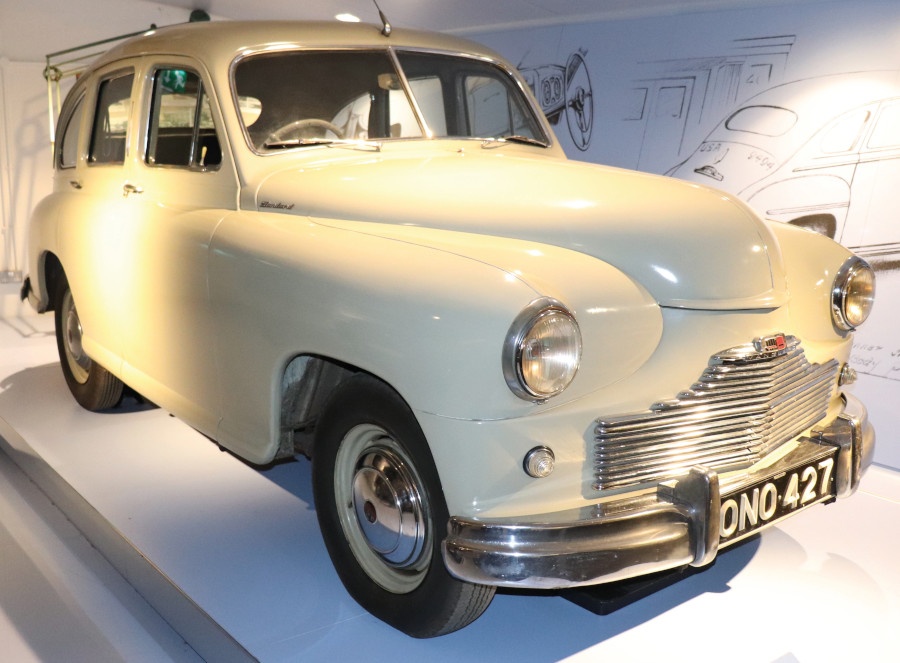

In 1948, Standard was the first major British manufacturer to release a truly all-new post-war car: the Vanguard. It retained the sloping rear end – leading to it often being referred to as the ‘beetle-back’ – but the rest was all new, with a heavy American styling influence. The 2.1-litre engine was a tuned-up version of the wet-liner four-cylinder being fitted to Ferguson tractors. It replaced all the other Standard models, but most of the early production was sent for export.

1955 Standard Eight (note- no external bootlid!)

1956 Standard Vanguard Phase III

1948 Standard Vanguard (Coventry Transport Museum)

1952 Standard Vanguard Phase 1A estate (Andrew Bone)

After becoming the first car to be optioned with the Laycock de Normanville overdrive in 1950, and a slight facelift in 1952 that introduced the heavy single-bar grille, the Vanguard didn’t change much until 1953. In that year, the oddly-proportioned Phase II Vanguard debuted, with a redesign that abandoned the beetle-back in favour of a conventional boot that looked as if it were tacked on as an afterthought. It was joined by a new Standard Eight, the cheapest four-door saloon on the market, powered by the new SC overhead valve 803cc engine.

The Eight was joined by the Ten in 1954, the same body with a 948cc engine, and supplemented by the Pennant, a slightly better styled and appointed 10, in 1957.

Meanwhile, in 1954, the Phase II Vanguard would be the first British car offered with a diesel engine from the factory. Again, the diesel engine was borrowed from Ferguson, and, with 40bhp, took a little over half a minute to reach 50mph from rest. Diesel engines in cars … it’ll never catch on.

A more major change in 1954 came with the departure of Sir John Black. He’d been appointed chairman in 1953, but was involved in a crash while test-driving a Swallow Doretti later that year. The board believed that his mental health had been impaired by the accident, and he was all but forced to resign in January 1954. Black’s long-standing deputy and PA, the impeccably named Alick Dick, took over as MD, and Air Marshal Lord Tedder was appointed Chairman. They began looking for partners to help expand Standard-Triumph, and began negotiations with the Rootes Group, Rover, Chrysler and Renault, but nothing came of it.

At the 1955 Motor Show, Standard unveiled the Phase III Vanguard, a modern, handsome unibody four-door saloon, still with the 2.1-litre four, but tuned up to 68bhp. It was joined in 1956 by the Vanguard Sportsman whose engine produced 90bhp with some tuning gear borrowed from the TR3, then in 1957 by the Michelotti-styled Ensign, lower-spec budget Vanguard with a 1,670cc engine. Michelotti also styled the facelifted Phase III, now called the Vignale, in 1958, and the 1962 Ensign DeLuxe, with the 2,138cc motor.

By 1959, the company had sold off all its tractor interests, including the Banner Lane plant, to Massey-Ferguson, and changed its name to Standard-Triumph International to coincide with the debut of the new Triumph Herald. Triumph had spent the Fifties becoming an exciting, sporty brand, eclipsing Standard’s rather dowdy image. The new Herald replaced the Standard Eight, Ten and Pennant.

1958 Standard 10 Companion estate (Andrew Bone)

1958 Standard Ensign

1958 Standard Vanguard Vignale (AUS)

1959 Standard Atlas Camper Van (Coventry Transport Museum)

At the very end of 1960, Standard-Triumph was bought out by Leyland Motors Ltd. Tedder left his chairman’s position, and, in the summer of 1961, when it was shown that Standard was making hefty losses, Alick Dick also “resigned” after a Leyland board reshuffle. At the time, the only Standards left in production were the Ensign and the Vignale; the Ensign was replaced in 1962 by the six-cylinder Ensign DeLuxe, and the Vignale by the Vanguard Six in 1961. The latter used a new 1,993cc, six-cylinder version of the old overhead-valve Standard SC four-pot, which would be the powerplant for the new-for-1963 Triumph 2000 saloon. Ironically, this would be the car that killed Standard – as the spotlight fell on the beautiful, Michelotti-penned saloon, Leyland quietly closed down Standard and put in a cupboard.

The last Standard, an Ensign DeLuxe, was built in May 1963. Leyland and Standard-Triumph merged with British Motor Holdings in 1968 to form BLMC, which later became British Leyland and all the horror that entails. In August 1970, the Standard name was lost altogether as the brand reverted to Triumph Motor Company, which blundered on until 1984. The Standard SC four-pot engine lived until the Spitfire, Dolomite and MG Midget ended in 1980; the straight-six powered the Triumph saloons, the Vitesse, GT6 and TR6 until the 2000 and 2500 were phased out in 1977. Production at Canley ended in 1980, and the factory was demolished in 1996.

The name lived on in India, though, as Standard Motor Products of India Ltd made a version of the Herald called the Standard Gazel until 1977, then reintroduced the name with the Standard 2000 – a Rover SD1 body with a barely-modified old 1,991cc Vanguard engine – in 1985. It only lasted until 1988, though the Bombay factory wasn’t officially closed until 2006, when the Standard brand finally died.

1960 Standard Ten 6cwt pick-up export model (Brian Snelson)

1970s Indian Standard Gazel MkII

BMW acquired the rights to Standard and Triumph when they bought out the Rover Group in 1994, but the Standard name went with British Motor Heritage when they sold that off in 2001. BMH own all the rights to the Standard name and trademarks, but there doesn’t seem to be any sign of life from this loved and trusted old British marque thus far, nor any in the future…